Bigger than baseball: The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum

Negro Leagues Baseball Museum preserves pivotal, often-untold history of baseball and race

Among the displays at the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum is a fairly ordinary photo of an 18-year-old Henry “Hank” Aaron holding a duffel bag as he stands at a train station in Mobile, Alabama, in 1951. He’s about to leave home, likely for the first time, to play baseball with the Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro American League. Visitors frequently have an a-ha moment at this very spot in the 10,000-square-foot museum in downtown Kansas City, Missouri.

“Because you know what Henry Aaron accomplished at the major league level,” says Bob Kendrick, director of the museum and a lifelong fan of the iconic home-run hitter and Hall of Famer. “He is one of the great Major League Baseball players of all time, but many of our visitors have no idea that his illustrious professional baseball career began in the Negro Leagues.”

Hammerin’ Hank, the nickname he earned during two decades of playing for Major League Baseball (MLB) teams in Atlanta, Georgia and Milwaukee, Wisconsin, was the last player to see time in the Negro Leagues and MLB. His presence in the museum, along with fellow stars, Jackie Robinson, Willie Mays, Ernie Banks, Satchel Paige, and Josh Bell, helps validate the competitiveness of and impact on the game of the many unknown Negro Leaguers whom visitors will learn about during a visit.

Saving and sharing this sometimes-forgotten era of baseball is the mission of the museum, which opened in 1990 in a one-room office. Beyond celebrating 30 years as a museum, the nonprofit is leading the national effort through 2020 and 2021 to commemorate the centennial of the Negro Leagues, which broke color barriers and gender barriers by welcoming Black, Hispanic and female players when major league baseball would not. Keep an eye on nlbm.com/centennial for rescheduled commemorations, which will range from special exhibitions and events at the museum to ballpark and community activities in MLB cities. Follow online activities by searching #NegroLeagues100 on social media.

Preserving the stories of the Negro Leagues is bigger than baseball. “Baseball history is American history,” says Kendrick.

“Sometimes lost inside this incredible story of these courageous athletes, who forged a glorious history in the midst of an inglorious time in American history, is the fact that this is a story about economic empowerment,” he observes. “This is a story about an unprecedented level of leadership within the African American community. And ultimately, this is the story of the social advancement of America.”

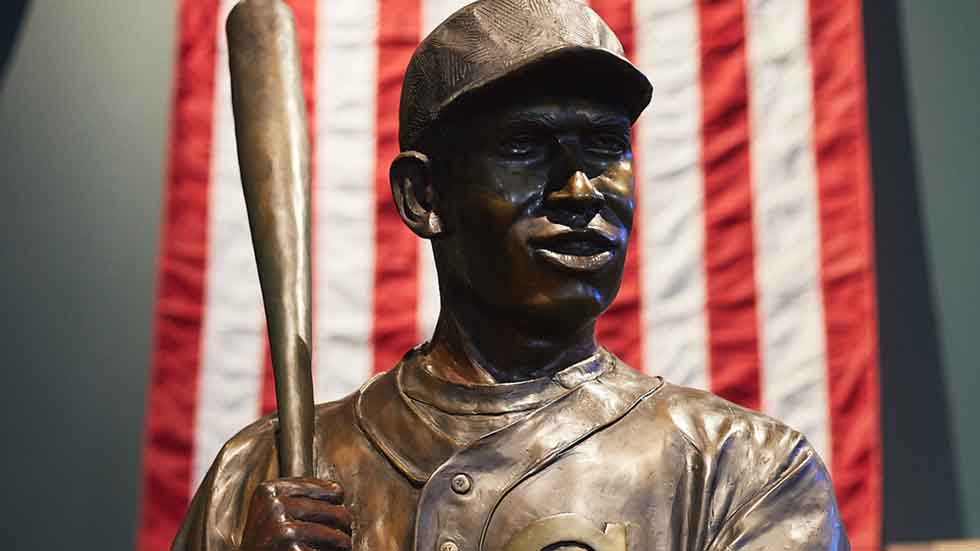

Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. Photo credit Visit KC

THE RISE AND FALL OF NEGRO LEAGUE BASEBALL

Just two blocks from the museum’s current home, a group of representatives from several Midwest ball clubs gathered on February 13, 1920, at Kansas City’s Paseo YMCA to form the Negro National League. African Americans had played baseball on amateur teams and even on a few professional teams with White players as early as the 1860s, but by 1900, legalized racial segregation forced them to build their own teams in order to play competitively. Andrew “Rube” Foster, a pitcher and Chicago team owner, led the effort to organize the top Black teams into a league and to energize Black players and administrators to take control of the teams to improve playing conditions.

Additional leagues were formed in eastern and southern states, and eventually they had a structure that mirrored MLB, including a world series.

The most widely known star, Satchel Paige, played in the league from 1926 until 1948, when he first pitched for MLB’s Cleveland Indians as a 42-year-old major-league rookie. It was Jackie Robinson, recruited after just one season in the Negro Leagues, though, who became the first African American in the modern era to play on an MLB roster. He joined the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947.

The Negro Leagues’ success with pushing integration to MLB was bittersweet, however, because it brought an end to the leagues. Negro Leagues baseball officially ceased operation in 1960, though many baseball experts consider the 1948 season as the final year that the level of play in the leagues equaled that of the major leagues.

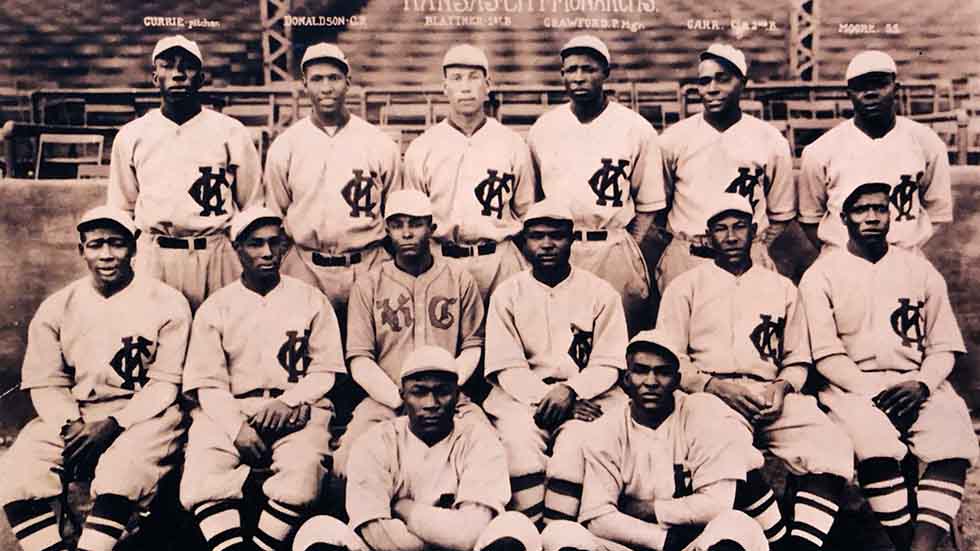

Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. Display of the 1921 Kansas City Monarchs. Photo Credit MeLinda Schnyder

A MISSION THAT’S ‘MORE IMPORTANT THAN EVER’

John “Buck” O’Neil spent seven decades in baseball, first as a player for the Negro League Kansas City Monarchs and, eventually, as a coach and scout in the big leagues. He was also a historian and ambassador for the sport and the Negro Leagues. In the late 1980s, he rallied the baseball and Kansas City communities to open the privately funded museum in the same community where the leagues started. Today, the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum is housed inside a cultural complex known as the Museums at 18th & Vine, which also includes the American Jazz Museum.

In addition to exploring a timeline that recounts both baseball achievements and national events, visitors can delve into numerous themed displays.

Barrier Breakers, new in 2020, highlights the 16 players, most of whom came up in the Negro Leagues, who broke their major league team’s color barrier.

“These players deserve to be more than just a footnote in baseball history,” Kendrick says. “A lot of people are surprised that it took 12 years before every major league team had at least one Black baseball player. And it didn’t get any easier for Elijah ‘Pumpsie’ Green to join the Boston Red Sox in 1959 than it was for Jackie Robinson in 1947.”

The Heroes of the Game section has a locker honoring each of the 36 Negro League and pre-Negro League players who have been inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Honorees range from players to influential executives, including Newark (New Jersey) Eagles co-owner, Effa Manley, who in 2006 became the Hall of Fame’s first female member.

Sponsored Content; Visit DestinationGettysburg.com to learn more.

Another impressive sight is some 400 encased baseballs, the world’s largest collection of single-signed baseballs with Negro Leagues player autographs on public display. The collection was purchased at auction for the museum by Geddy Lee, lead singer of the Canadian rock band Rush and an avid Toronto Blue Jays fan.

Beauty of the Game focuses on women in the league, from owners and managers to the three females who played alongside men in the 1950s. The Indianapolis Clowns signed Toni Stone in 1953 to replace Aaron when he moved into MLB’s Boston Braves organization. Stone, the first woman to play on a men’s professional baseball team, was joined by the league’s first female pitcher: Mamie “Peanut” Johnson (she went 33–8 against the men and hit .270 over three seasons). Connie Morgan replaced Stone when she was traded to the Kansas City Monarchs.

“Here’s a league borne out of segregation that would become the driving force of social change in this country,” Kendrick points out. “Here’s a league borne out of exclusion that would become perhaps this country’s most inclusive entity. They didn’t care what color you were, and they didn’t care what gender you were. The very league that was being treated contrary would not allow itself to behave in the same fashion. We’re still having, and must have, these much needed conversations around social justice and around gender equity. This is why I say our museum is more important today than ever before.”

Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, women of the negro leagues display. Photo Credit MeLinda Schnyder

COMMEMORATING 100 YEARS

Representatives from Major League Baseball and the Major League Baseball Players Association joined museum staff and local dignitaries at the still-standing Paseo YMCA building this past February, exactly a century after Foster’s meeting. The two MLB entities announced a joint $1 million donation to the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum to help renovate the former Y building into the Buck O’Neil Education and Research Center.

Officials anticipate that at least the administrative offices in the 40,000-square-foot center will open by the end of next year. When fully complete, the facility will include a sports science center where students can use baseball to learn math and science as well as a research library housing the leagues’ archives. While the facility is not yet open, it’s still worth stopping by to see the murals painted on the exterior of the building’s south side and to spend time on the miniature baseball field playing catch.

“It’s a beautiful backdrop with a great view looking west toward downtown Kansas City,” notes Kendrick. “You still get the opportunity to come there and stand on those historical grounds where this all started.”