Inside Oklahoma’s Remote Black Mesa State Park and Preserve

With prehistoric petroglyphs, dinosaur tracks, and more, this panhandle park makes the past present

The full fire-red moon rising over the mesa in the northwestern corner of Oklahoma looked ghostly, much like everything else in this scrubby wind-scorched desert land. One of the darkest spots in Oklahoma—and one of the most remote state parks in the nation—Black Mesa State Park and Preserve is situated where the Rocky Mountains meet the shortgrass prairie.

My friends and unofficial guides, Jeff Hargrave and Jack Fowler, a certified wilderness tracker, had been telling me for years that I should join them to see the stars, prehistoric petroglyphs and dinosaur tracks for which the park and preserve are famous. Finally, curiosity got the better of me, so my friend Emily and I loaded our camping gear one April weekend and headed to the tip of Oklahoma’s panhandle, where Colorado, New Mexico and Oklahoma kiss.

Black Mesa State Park and Preserve, named for the black lava that coated the panhandle 30 million years ago, is a place you have to want to go to. It’s 6 hours from my home in Oklahoma City along winding back roads. Guymon, the nearest town, is nearly an hour away; only the tiny settlement of Kenton, home to 16 stubborn souls, is nearby.

The dark that surrounds Black Mesa State Park makes it a popular spot for stargazing. Photo by Lori Duckworth/Oklahoma Tourism

The dark that surrounds Black Mesa State Park makes it a popular spot for stargazing. Photo by Lori Duckworth/Oklahoma Tourism

THE BIG DRAWS

In the 1800s, Oklahoma’s panhandle was considered “No Man’s Land” due to the harsh landscape. The beauty of the mesas and the sandstone terrain, however, could not be ignored, and the distinctive geography led to Black Mesa becoming a state park in 1959. Nearly 40 years later, 1,600 acres surrounding the park were added as a nature preserve to protect the mesa landscape and its rare plants and animals, including bighorn sheep, black bear and elk.

Today, the area remains one of the least populated in the state. Because of that isolation, thousands of amateur astronomers flock here for the Okie-Tex Star Party, a stargazing event held each September. Other visitors come for the dramatic views and the Native American and Western history seeped into the rocky terrain.

A granite obelisk marks the highest spot in Oklahoma at the end of the Summit Trail at Black Mesa State Park and Preserve. Photo by Heidi Brandes

A granite obelisk marks the highest spot in Oklahoma at the end of the Summit Trail at Black Mesa State Park and Preserve. Photo by Heidi Brandes

“Black Mesa is unique because there are two parts of it that are separated by 15 miles,” says Chase Horn of the Oklahoma Department of Tourism and Recreation. “You have all the usual state park stuff like camping, hiking and fishing, but the other part is the Black Mesa Nature Preserve itself.”

Before meeting up with Fowler and Hargrave, Emily and I hiked the 8-mile round-trip Summit Trail, huffing up steep inclines to the top of the mesa where a giant obelisk declares “Highest Point in Oklahoma—4,972.97 feet above sea level.” Below us, the mesa rolled out like waves in a sand-brown ocean.

Our next excursion was to see petroglyphs, so we guzzled the water the state park urges visitors to bring and hurried down to meet our guides.

A visitor studies petroglyphs carved into a rock at Black Mesa State Park and Preserve. Photo by Emily Brashier

A visitor studies petroglyphs carved into a rock at Black Mesa State Park and Preserve. Photo by Emily Brashier

PETROGLYPHS, DINOSAURS AND ELUSIVE COUGARS, OH MY!

That night, flashlights in hand, we hunted for petroglyphs while navigating barely-there trails on a side-by-side four-seat Polaris. With Fowler in the driver seat, the vehicle bounced along through the dark for a couple of miles from Hargrave’s cabin to a flat-faced boulder etched with what looked like a snake, a turtle and other unidentifiable scrawlings.

“These were made 3,000 years ago,” Hargrave noted as we studied the prehistoric graffiti. “It could have been a way marker, but we don’t know.” In fact, to this day, it remains unclear who made the art, or why.

Although we were with guides who had access to private land where these petroglyphs exist, visitors can book tours with The Hitching Post, a working ranch and guest lodge in Kenton, to see petroglyphs scattered at various private land sites near the reserve.

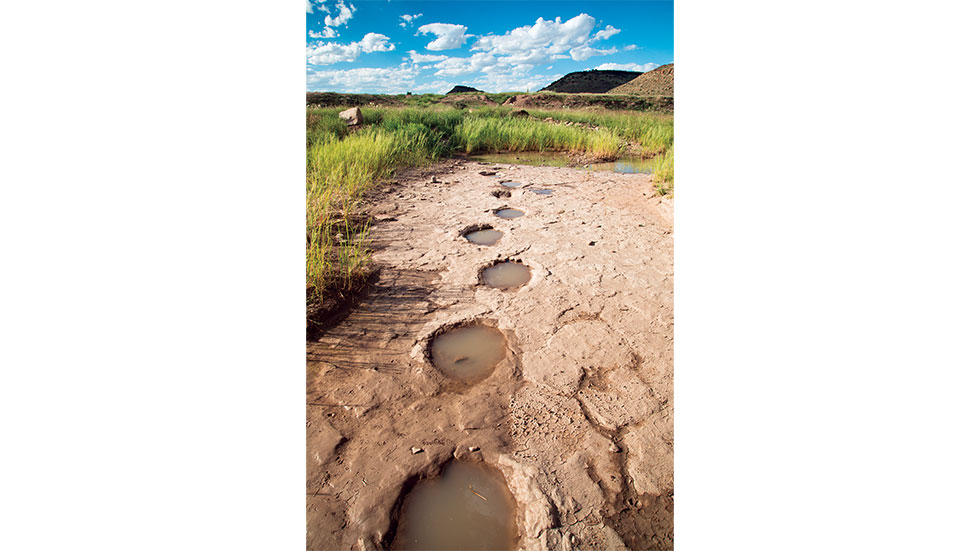

Ancient dinosaur footprints can be found at the Black Mesa State Park and Preserve. Photo by Kim Baker/Oklahoma Tourism

Ancient dinosaur footprints can be found at the Black Mesa State Park and Preserve. Photo by Kim Baker/Oklahoma Tourism

The heat of the spring day long gone, we shivered under blankets in the shocking cold wind of a desert evening. Before retiring for the night, Emily and I listened for the howling of coyotes, but they apparently weren’t in the mood to sing. The hard, rocky land was quiet—eerily so for those, like us, used to the constant rumble of city life—and we slept deep and hard.

Black Mesa isn’t just a place of ancient carvings; it’s also a depository of dinosaur fossils. Dinosaurs lived here during the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous period. You can visit the original dinosaur quarry, marked only with a hand-painted sign and a concrete replica of a massive dinosaur femur uncovered there, on Route 325 between Black Mesa State Park and Kenton. The original and subsequent digs yielded more than 18 tons of dinosaur bones, according to the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Carved into the sandstone at Black Mesa State Park and Preserve are petroglyphs made by ancient Native American people. Photo by Emily Brashier

Carved into the sandstone at Black Mesa State Park and Preserve are petroglyphs made by ancient Native American people. Photo by Emily Brashier

We also searched out dinosaur tracks among the dry creek beds in and around the preserve. One such trail of tracks can be seen on private land at Carrizo Creek, located half-mile north of the Summit Trail marker. The landowner allows visitors to access the property to see the round prints that were made roughly 150 million[1] years ago. At another creek bed in the preserve, we saw a line of turkey-like tracks forever imprinted on the rocks.

“That’s a Coelophysis,” Hargrave noted. “It was one of the first dinosaurs ever to roam the area.”

We also found modern footprints of bobcat, bear, coyote and even cougar on our hike. “I’ve seen the prints, but I’ve never seen the mountain lion,” Fowler said. “But he’s out here.”

The new Kenton Mercantile comprises a restaurant and a store selling food and sundries. Photo by Heidi Brandes

The new Kenton Mercantile comprises a restaurant and a store selling food and sundries. Photo by Heidi Brandes

We spent time exploring abandoned homestead sites and sandstone pillars called hoodoos, strangely shaped towers of wind-sculpted sandstone that loom in groups all over the park. We then made tracks of our own to stop at a marker 1.4 miles north of the Summit Trail—the very spot where Oklahoma, New Mexico and Colorado touch.

We finished our day with a simple meal at the newly-opened Kenton Mercantile, a small—and the town’s only—restaurant that’s also home to a shop selling food and sundries.

As we departed, Fowler turned to me and asked, “Do you see why we love it out here?”

“Oh, yeah,” I said, staring out where dinosaurs once roamed and Fowler’s elusive mountain lion still prowled. The mesa was ghostly in the quiet darkness, and I felt as if we were the only people under that vast lonely sky. My answer was as evident as that full moon. “I definitely do.”