North Dakota’s Theodore Roosevelt National Park

The ‘other’ Badlands offers history and stunning scenery—and fewer visitors than its South Dakota cousin

When it comes to travel, experience has taught me that the smoothest way through a patch of clouds is to search for the silver lining. While planning a cross-country road trip during the COVID-19 pandemic, my husband and I kept encountering figurative roadblocks. Our planned route kept shifting as we sought to avoid the ever-changing tableau of virus hotspots. We also needed to contend with the fact that many museums and other attractions along the way were temporarily closed, and the well-known national parks were full to bursting with visitors.

We ended up choosing a route cutting through relatively uncrowded North Dakota, resigned that we’d miss out on some iconic scenic spots such as Mount Rushmore in South Dakota. But then we spotted Theodore Roosevelt National Park on the map. We weren’t familiar with the destination, but we figured anything bearing “national park” status was worth a look. And it was.

Tucked in the far western part of the state near the Montana border, Theodore Roosevelt National Park (TRNP) boasts spectacular scenery, much like the famous vistas found in Badlands National Park about 300 miles away in South Dakota. Yet TRNP gets 690,000 annual visitors, according to the National Park Service (NPS)—300,000 fewer visitors per year than its cousin, with most of that difference occurring during the summer months—making it an appealing road trip destination for those seeking some solitude.

THE ‘CONSERVATIONIST PRESIDENT’

The park was established in 1947 to honor the first President Roosevelt (in office from 1901 to 1909), who credited time spent ranching and hunting in this area of North Dakota with awakening him to the need for preservation of America’s natural resources. The ranchland owned by Roosevelt in the late 19th century is now part of the 70,000-acre property that was elevated to full national park status in 1978.

Often called “the conservationist president,” Roosevelt signed into law the Antiquities Act of 1906, giving the president discretion to “declare by public proclamation historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic and scientific interest...to be National Monuments.” Unlike national parks, which required congressional approval, presidents could now establish national monuments easily. Through this act, Roosevelt preserved nearly 20 treasures between 1906 and 1908, including the Grand Canyon, Muir Woods and Devils Tower.

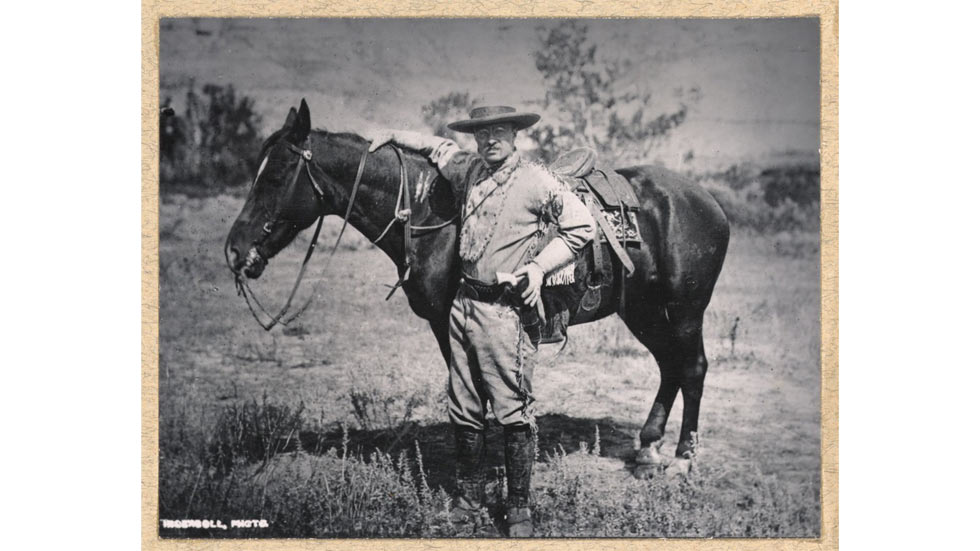

A young Theodore Roosevelt on his North Dakota ranch, circa 1880s; Photo courtesy of National Park Service

AN OTHERWORLDLY LANDSCAPE

As my husband and I drove westward from Minnesota along Interstate 94 in central North Dakota, the terrain changed from pancake-flat in the east near Fargo to rolling hills in the center of the state near Bismarck. As we neared “Roosevelt country,” we glimpsed barren hillsides striped with bands of minerals that looked like a set from a Star Wars movie. We had entered North Dakota’s badlands.

Called “badlands” because the terrain was considered difficult to travel (the native Lakota people referred to this area as mako-sica, which translates roughly to “bad lands”), this geological anomaly was formed when layers of sedimentary sandstone, limestone and shale created by volcanic eruptions millions of years ago were exposed due to weathering and erosion, creating stark buttes with stripes of white, rust and bluish gray.

Despite this harsh landscape, certain plants and animals have adapted to make this place their home. The northern slopes of the buttes are forested with Rocky Mountain juniper, sheltering herds of elk and bighorn sheep. The Little Missouri River snakes through the park, quenching the thirst of porcupines and other small mammals that enjoy the shade of cottonwood and elm trees along the river’s banks. In between, grasslands in a range of greens and yellows provide forage for mule deer and herds of bison. Several prairie dog colonies, or towns, populate these lowlands, where the highly sociable burrowers form a network of tunnels for protection from predators.

A herd of bison grazing in the grassland adjacent to the Little Missouri River; Photo by Larissa C. Milne

ONE PARK, THREE UNITS

Because the 70,000 acres of TRNP are not contiguous, the park comprises three distinct units: the South Unit, the North Unit and the Elkhorn Ranch Unit; the latter is the 218-acre grassland site of Roosevelt’s former ranch. The Little Missouri River is a lifeline connecting the three sections.

The South Unit, which consists of roughly two-thirds of the park’s acreage, is the easiest to access; its southern boundary skirts Interstate 94 just west of Dickinson, North Dakota. This unit receives nearly 75 percent of the park’s annual visitors, reports the NPS.

We ventured farther to the park’s North Unit, a 68-mile drive from the South Unit up US Route 85. Both units offer scenic drives that wind past badlands with multiple overlooks and interpretive stops, along with access to picnic groves and trailheads leading to hiking trails and campgrounds. With fewer than 20,000 visitors per month, the North Unit offers the best chance to explore the scenery with nary an effort needed to maintain social distancing.

A viewing structure overlooking the Little Missouri River provides the perfect perch for a moment of solitude; Photo by Larissa C. Milne

Our strategy worked: There was no wait at the entrance gate, and we saw no more than a dozen other vehicles during our visit. We particularly enjoyed the Oxbow Overlook above a bend in the river, which at 2,400 feet provided a view of the badlands for miles. At River Bend Overlook, we took shelter from the sun in a structure built by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s, while there, we marveled at the greenery that managed to eke out a living in these austere conditions.

Farther along on our drive, a herd of bison, oblivious to us, grazed in a nearby pasture as we ogled a series of refrigerator-size sandstone spheres known as the Cannonball Concretions, calling to mind the striking geological phenomena that helped shape this unusual part of the world.

As we drove away, we spied a dusky thundercloud in the distance rolling across the vast prairie and jagged streaks of lightning piercing the sky. After our experience at this magnificent park, we viewed those streaks differently: no longer ominous, they reminded us of the cloud’s silver lining.

Top photo courtesy of National Park Service.