US Armed Forces Museums

Official museums of the US Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, and Coast Guard honor our service members while telling their stories

I always knew that my father, the late Robert N. Gawlas Sr., had served in the Navy. He sported a tattoo on his left forearm, something of a novelty when I was a kid in the 1960s and ’70s.

The anchor and rope image came courtesy of a shipmate during World War II, a longtime Navy tradition.

My dad had enlisted in February 1943 at the age of 17. The US needed to ramp up its fighting force quickly, and my dad saw service as his duty. Mechanically adept, he worked as a machinist mate first class in the engine room of the USS Warren in war in the Pacific until his honorable discharge in March 1946.

He enrolled in the Navy Reserve, and when the Korean War began in 1950, my dad was called for 15 more months of active duty, this time in the engine room of the USS Hamul.

The writer, Theresa Medoff's late father, Robert N. Gawlas Sr.

I never recall my dad talking about his time in the service. My mother, Theresa Gawlas, says he never did. His younger sister, my Aunt Margie Bogdan, saved his letters home. In one, he recounts the terrifying experience of Japanese kamikazes targeting the Warren. My dad was so nervous, he wrote, that he bit his “fingernails up to the elbows.

It’s too late for me to ask my dad about his time in the Navy, and perhaps he wouldn’t want to talk about it even now. But it’s not too late for me and others who have had a spouse, parent, child, sibling or other loved one serve in the US military to learn more about their service and to better understand the fullness of who they are and what they have experienced.

Archival records sometimes yield only dry accounts, but you can supplement that with a visit to the official museums of the US Army, Marines, Navy, Air Force and Coast Guard. As we mark Veterans Day 2021, AAA World highlights those museums and the stories they tell, with deep appreciation for our active, reserve and veteran members of the US Armed Forces.

NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE UNITED STATES ARMY I NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS I NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE UNITED STATES NAVY I NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE UNITED STATES AIR FORCE I US COAST GUARD MUSEUM

National Museum of the United States Army; Photo courtesy of Duane Lempke, National Museum of the United States Army

SOLDIER STORIES: NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE UNITED STATES ARMY

Fort Belvoir, Virginia

By Michael Milne

I stared into the eyes of an American soldier perched in the gunwale of a Higgins boat bobbing in the English Channel. Above him, another dozen soldiers scrabbled down a rope ladder dangling from a troop carrier to join their platoon mates in the landing craft. Although I was standing safely in the National Museum of the United States Army—and not battling waves off the coast of France on June 6, 1944—the fear, anxiety and determination in those eyes were palpable.

The Army’s new museum conveys an expansive history, yet it remains focused on individual soldiers, telling their stories, in part, through combat matériel that spans the centuries, from a sword wielded by US Army Capt. John Berry during the British bombardment of Fort McHenry in Baltimore during the War of 1812, to a Huey helicopter gunship flown in Vietnam, to a broken watch recovered from the rubble of the 9/11 attack on the Pentagon.

The National Museum of the United States Army opened last year on Veterans Day. It contains 11 galleries arranged chronologically, beginning with our nation’s founding and extending to today’s complex world, and uses some 1,400 artifacts to relay the story of the US Army.

A Sherman tank similar to those that fought in the Battle of the Bulge; Photo by Larissa Milne

The museum appeals to a range of visitors, from those eager for high-tech, hands-on simulations, to those who prefer reading placards chock-full of information, to those captivated by dioramas of soldiers in action.

Those soldiers’ personal stories appear throughout the exhibits. They include Specialist Lori Ann Piestewa, a member of the Hopi Tribe from Arizona who was ambushed and captured while on convoy duty in Iraq and later died of her injuries; 1st Lt. Charles Bailey, a pilot with the Tuskegee Airmen, the Army’s first Black military airmen, who was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross; and Sgt. Enoch Kanaya, a Japanese American who fought in the Italian campaign of World War II.

Multimedia displays throughout the galleries bring different periods of history to life through video and audio. Press a button for Civil War music, for example, and the 1863 song “When Johnny Comes Marching Home” plays.

That familiar melody represents the universal longing of soldiers, including that lone GI setting off to storm the beaches of Normandy, to make it home safely. After a day in this inspiring museum, you’ll depart with renewed appreciation for the men and women who have served in the US Army. TheNMUSA.org; 800/506-2672

Lifelike displays throughout the National Museum of the US Marine Corps depict US Marines in action; Photos courtesy of National Museum of United States Marine Corps

UNCOMMON VALOR: NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS

Triangle, Virginia

By Renee Sklarew

Determination, focus, stoicism. These emotions play on the faces of the lifelike figures of five Marines attempting to breach a wall on the South Pacific island of Tarawa in 1943. Two of the Marines are atop an amphibious tractor. An injured Marine on the beach grips his bloody leg, while two others move in tandem toward the unseen enemy.

This tableau is one of several that stop me in my tracks as I enter the National Museum of the Marine Corps, adjacent to Marine Corps Base Quantico. Such depictions of courage repeat throughout the museum.

Even the soaring atrium, visible from Interstate 95, pays homage to a formidable moment in history: when six Marines raised the American flag during the Battle of Iwo Jima.

Opened in 2006, the museum presents more than 200 years of Marine Corps history in seven large galleries. The galleries focus primarily on the role of Marines during wartime, from Defending the Republic in the Colonial-era, to the Vietnam War. New exhibits, which opened in 2020, showcase the Marines’ involvement in noncombat and humanitarian missions. Every scene in the museum is inspired by first-person accounts.

In the Making Marines gallery, I metaphorically walk in a Marine’s shoes by lining up to enlist, hearing the drill instructor bark orders and preparing to board a bus for boot camp. Inside the World War I gallery, war correspondent Floyd Gibbons huddles over his typewriter in Belleau Wood, a forest in France, as mortars blast around him. Gibbons lost his left eye in the battle.

When I enter the Korean War gallery, I notice the temperature has dipped significantly in a re-creation of the frozen Chosin Reservoir, site of the coldest battle ever fought by Marines. The darkened Vietnam gallery reveals Marines tending to their wounded. Here, I can feel hot air circulated by Huey helicopter rotors and hear the deafening sounds of artillery.

It’s all utterly gripping, but for me, the most moving experience was watching the videos of spouses, siblings and parents of active-duty Marines describing the sacrifices they’ve made during their loved one’s deployment. And the real flag raised over Iwo Jima takes my breath away.

“The museum’s exhibits portray the fact that war is not pretty, and we aren’t going to make it look like it is,” says Public Affairs Chief Gwenn Adams. “What makes us different is, yes, we have artifacts, and we tell stories, but it’s so much more than the history of the Marine Corps. It’s the personal stories of those who have given so much to establish and maintain our way of life, to maintain a nation that exists for all people.” usmcmuseum.com; 877/432-1775

The fighting top of the USS Constitution displayed at the National Museum of the US Navy; Photo by Renee Sklarew

MARITIME MIGHT: NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE UNITED STATES NAVY

Washington, DC

By Renee Sklarew

When I walk into the National Museum of the United States Navy, looming before me is the mast from the iconic USS Constitution, famous for its role in the War of 1812. Beside that fighting top stands an imposing section of the black-painted wooden hull of the ship nicknamed “Old Ironsides,” complete with cannons and rigging. Surrounding me are intricate ship models, torpedoes, gun turrets and countless other artifacts that illustrate how the US Navy has protected our country since 1775.

As one of the oldest military museums in the US, the Navy museum has a collection that spans the Colonial period to the present. While I knew that the Navy played a vital role in wartime, I also discovered some naval history that surprised me. Did you know, for example, that Navy sailors have explored the deepest ocean and walked on the moon?

From Admiral Richard Byrd and the Navy’s early polar explorations to Lt. Don Walsh, who in 1961 traveled 35,000 feet deep into the Mariana Trench on the bathyscaphe Trieste, Navy expeditions and personnel have helped to map the world’s oceans.

And in the exhibit “Fly Navy to the Moon,” I learned how the Navy partnered with NASA on space exploration and that early Apollo astronauts were trained naval aviators.

Interestingly, the museum in southeast DC is located on the grounds of the Washington Navy Yard. George Washington set aside this land for a Navy base, and it has operated continuously in this capacity since 1799.

The bathyscaphe Trieste, which traveled to the bottom of the Mariana Trench; Photo by Renee Sklarew

The museum’s indoor exhibits are housed in Buildings 70 and 76, former ship-building facilities. Just outside these buildings is Willard Park, a grassy square overlooking the Anacostia River. The museum displays its largest relics there, including a 36,000-pound propeller from the WWII battleship USS South Dakota.

Because the museum is on base, admittance is strictly controlled. You’ll need to show a US government-issued REAL-ID and your vehicle registration, and you will be fingerprinted and photographed before you can tour the museum. Details can be found on the museum website.

Though filled with maritime history, the Navy museum is not as interactive and visitor-friendly as the newer Army and Marine museums. That will soon change. A modernized version of the museum is in the planning stages, with an anticipated opening for the Navy’s 250th anniversary in October 2025.

The future museum will be easy to access because it will be located outside the base, says Museum Director Dr. James Rentfrow. I can’t wait to see the immersive displays and 4D theater productions. They promise a dramatic accounting of the sacrifices and achievements made by American sailors past and present. history.navy.mil/content/history/museums/nmusn.html; 202/685-0589

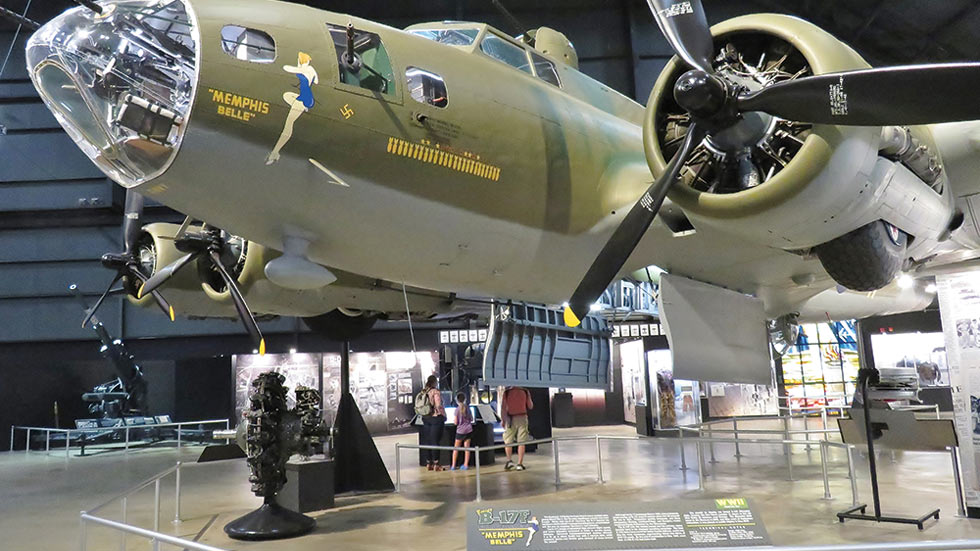

Memphis Belle; Photo by Damaine Vonada

AIMING HIGH: NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE UNITED STATES AIR FORCE

Wright-Patterson Airforce Base, Ohio

By Damaine Vonada

At the National Museum of the United States Air Force, visitors frequently fixate on the bathing-suited beauty painted on the front fuselage of the Memphis Belle. Her pinup pose indicates why Capt. Robert Morgan named the B-17F he piloted in World War II for his sweetheart in Tennessee, but the 25 bombs pictured beside her explain the plane’s honored place in the museum.

B-17s are renowned for their key role—and the horrific losses they suffered—in the highly successful strategic bombing raids the US Army Air Forces (the Air Force’s forerunner) and its Allies conducted over Europe to clobber Nazi Germany’s war machine.

Enemy fighters shot down 80 percent of Memphis Belle’s bomb group during her first three months of sorties. Battered by flak and bullets, Memphis Belle lost engines repeatedly during her six months of combat service and on one occasion even wobbled back to base in England minus most of her tail. No wonder radio operator Technical Sergeant Robert Hanson kissed the ground in May 1943 after Memphis Belle defied the odds and survived 25 missions.

Afterward, plane and crew crisscrossed the US on a triumphant war bonds tour that drew huge crowds and made Memphis Belle a symbol of courage and sacrifice. Today, the plane ranks among the museum’s most precious possessions.

“Memphis Belle represents 30,000 airmen who died over Europe,” says Curator Doug Lantry. “It’s the Air Force equivalent of the Iwo Jima Memorial.”

A replica of Vittles, the dog who flew along during the Berlin Airlift missions; Photo by Damaine Vonada

The National Museum of the U.S. Air Force, located five miles from Dayton, is the world’s largest military aviation museum. Its 19 acres of galleries chronicle manned flight from the airplane’s invention by Daytonians Orville and Wilbur Wright to the high-tech B-2 stealth bomber. Displays include more than 350 aerospace vehicles and artifacts ranging from Morgan’s dog tags to brightly painted sections of the Berlin Wall.

A recording of Lt. Milton Ashkins’ 1941 Mayday as he crash-landed his O-38 in Alaska underscores the risks Air Force personnel face, while the parachute made for Vittles, the dog who flew along during Berlin Airlift missions delivering food to starving Germans, highlights the humanity of their service.

For examples of valor, you need only look to the more than 50 Airmen awarded the Medal of Honor. They include Staff Sergeant William Pitsenbarger, who flew on nearly 300 rescue missions in the Vietnam War. His last mission was in 1966 when the pararescueman volunteered to be lowered into the midst of a firefight to treat and help evacuate wounded soldiers. As the rescue helicopter filled, Pitsenbarger gave up his place so that one more wounded soldier could be airlifted. Pitsenbarger’s body was found the following day. He was 21. nationalmuseum.af.mil; 937/255-3286

Medal of Honor awarded posthumously to Signalman First Class Douglas A. Munro; Photo by Bob Curley

STANDING READY: US COAST GUARD MUSEUM

New London, Connecticut

By Bob Curley

The first placard you read upon entering the US Coast Guard Museum says that Coast Guard members serve “often without recognition of their efforts.” It’s likely true that many civilians don’t understand the full range of the contributions made by the Coast Guard, which serves as first responder, federal law-enforcement agency and military force. A visit to this museum on the Coast Guard Academy campus should change that. Like the Coast Guard itself, the museum is small yet powerful.

The US Coast Guard traces its history to 1790, eight years before Congress established the Navy Department. Its members have served in nearly all of the nation’s armed conflicts, but they are better known for rescuing boaters and operating navigational aids such as buoys and lighthouses.

“Anyone who is a sailor has either met the Coast Guard or been saved by the Coast Guard,” says Petty Officer 2nd Class Lauren Laughlin, curator of the museum. “When you go to the other military museums, you’re learning about things that happened in Europe or the Pacific. The Coast Guard works to save American lives every day.”

Planning is underway for a large, contemporary National Coast Guard Museum to open in 2024 on the historic waterfront in New London (coastguardmuseum.org). In the meantime, the museum at the Coast Guard Academy smartly navigates the branch’s evolution from the 18th-century Revenue Cutter Service, established to enforce tariff and trade laws and prevent smuggling, to a modern service branch with more than 1,800 vessels, 200 aircraft, 50,000 members and patrols that reach around the globe.

Coast Guard history is often as fascinating as it is forgotten. You’ll learn, for example, that USRC Harriet Lane was the first warship to fire a shot in the US Civil War. You’ll also discover that during World War II, “Coasties” delivered troops to the beaches of Normandy on D-Day.

Medal of Honor awarded posthumously to Signalman First Class Douglas A. Munro; Photo by Bob Curley

The museum’s on-campus location means fellow visitors are just as likely to be uniformed service members as curious civilians. It also means you’ll need to pass through security at the entrance gate. Bring your government-issued photo ID (as well as your vehicle registration and proof of insurance if you drive). Find details at uscga.edu/visit-cga.

Amid exhibits detailing operations against pirates and drug smugglers are a flat-bottomed boat used to rescue Louisiana residents in 2005 during Hurricane Katrina, massive lighthouse lenses, and the original wooden figurehead from the USCGC Eagle, the academy’s 295-foot training ship.

The most prized possession in the collection is also among the smallest: the Medal of Honor awarded posthumously to Signalman First Class Douglas A. Munro, who led a daring 1942 water evacuation of trapped Marines from Guadalcanal in the South Pacific. Shockingly, it’s the only Medal of Honor ever awarded to a member of the US Coast Guard.

As this revealing museum demonstrates, however, despite such slights, the “long blue line” continues to live up to its motto Semper Paratus, “Always Ready.” history.uscg.mil/museum; 860/444-8511