Normandy Travel Guide: D-Day Remembrance and Artistic Treasures

The 80th anniversary of the D-Day landings presents the opportunity to trace the footsteps of allies and appreciate the artistic beauty of Normandy’s landscape

I’m huddled in a chilly mist as the tide rolls across the sands of Omaha Beach, one of two amphibian landing sites for American soldiers on D-Day. Eighty years earlier, GIs had slogged through crashing waves as gunfire erupted around them. I shivered, not just from the cold, but also from the lingering presence of 2,500 Americans who sacrificed their lives that day.

My grandfather had died during a training exercise in 1942, and his younger brother’s submarine vanished off the coast of Japan nine months later. I married an Air Force Academy graduate who studied military history. My husband, Jeff, had watched the HBO miniseries Band of Brothers at least four times. It focused on the history of Easy Company, a now-renowned parachute infantry regiment that forged powerful bonds through the crucible of the Second World War. We always wanted to pay our respects to the men who sacrificed their lives and thank the veterans who survived the war. It’s estimated there are only 30 D-Day veterans currently living, and most of them are over the age of 100.

While time diminishes personal connections to the war, the elements erode Normandy’s significant WWII sites. These include a German bunker perched on a crumbling cliff and the ebbing remains at Arromanches of the concrete “Mulberry” harbors, artificial piers that facilitated the delivery of key supplies. Because of these inevitable losses, I felt a sense of urgency to visit important sites along Normandy’s northern coastline. So, this past winter, my husband and I set out on a seven-day journey.

D-Day 75 Garden at Arromanches; Photo by Shelly Steig

HONORING THE SACRIFICES

Normans show their appreciation of Americans by flying Old Glory from private homes, erecting memorials to soldiers in town squares and plastering mural-size photos of Allied troops on buildings. The region salutes the landings each June during D-Day Festival Normandy, and every 10 years, the French government organizes an international ceremony attended by heads of state and veterans. The 80th anniversary takes place this June 1 through 16.

So many museums and permanent memorials commemorate the liberation that my husband and I could have spent a week concentrating on them alone. At Caen Memorial Museum, our first stop, I learned how overconfidence on Germany’s side and cunning on the other side impacted D-Day. Hitler believed attacks would land in Calais, the shortest distance across the English Channel from Great Britain. Allied commanders took advantage of this certainty by placing a full-scale phantom army, including inflatable rubber tanks and cardboard landing craft, along that coastline. While watching archival footage, I was moved by videos of Higgins boats packed with brave men who smiled at the camera. My tears began to flow when I saw images of civilians kneeling to pray over the bodies of fallen soldiers.

After Caen, we drove to the medieval village of Bayeux, a wonderful hub from which to explore. We started at the city’s Memorial Museum of the Battle of Normandy near the British Normandy Memorial. Through immersive experiences, the museum follows chronologically from the day after the landings until August 29, 1944. At Longues-sur-Mer battery, part of Hitler’s allegedly impenetrable Atlantic Wall, we climbed through three German bunkers and a command post clinging to the cliff. Then, on the advice of the tourism office, we followed our GPS to WN60, a little-known Wehrmacht strongpoint that overlooks Omaha Beach. No one else was there as we walked beside now-shallow zigzag trenches to machine gun nests and a bunker.

Fans of Band of Brothers will recognize Sainte-Mère-Église, one of the first villages freed from German occupation. A replica parachutist dangles from the town church’s spire, highlighting an actual incident explained at the nearby Airborne Museum. The museum salutes American paratroopers and allows a glimpse into what it was like to float into the fog of war.

Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial; Photo by david-bgn/stock.adobe.com

Jeff and I stood at attention for the lowering of the flag at the Normandy American Cemetery, where 9,387 GIs are interred, including 45 pairs of brothers. I teared up again as archival footage surrounded us at Arromanches 360, a circular theater near a memorial garden with ghost-like sculptures. By then, I’d used all the tissues I brought from home, so I knew it was time to take a respite.

Pointe du Hoc; Photo by AUFORT Jérome/stock.adobe.com

DRAWN BY THE LIGHT

Even as we walked the landing beaches with their remnants of war and looked over the bomb-pocked cliffs of Pointe du Hoc, I could understand why, in 1864, Monet had written of this landscape, “It is beautiful here…every day I discover even more beautiful things. It is intoxicating me, and I want to paint it all.”

After experiencing the ugly realities of war, it was important for me to see the beauty of Normandy through the eyes of the Impressionists. These included Camille Pissarro, Eugene Boudin and, most famous of all, Monet. Monet and his peers could have stayed in Paris, yet they chose Normandy as their muse. Its medieval villages, white sandstone cliffs and sweeping countryside beguiled them, as did its moody weather and ever-changing light that interplayed with the waters of the English Channel and the Seine.

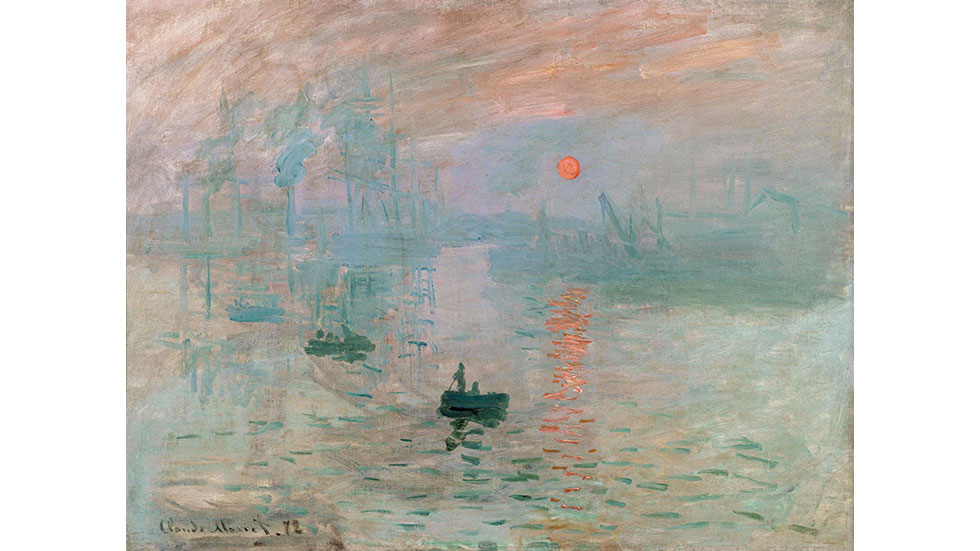

Impression, Sunrise by Claude Monet; Photo by GiorgioMorara/stock.adobe.com

Many historians credit Pissarro and Boudin as the grandfathers of the Impressionists; however, Monet gave the movement its name. His 1872 painting of Normandy’s Le Havre harbor, Impression, Sunrise, shocked critics, one of whom wrote, “Wallpaper in its embryonic state is more finished than that seascape.” Despite the harsh criticism, the brave creators stubbornly refused to color inside the lines.

Impressionists balked at the traditional, hyper-realistic works that elite juries from the prestigious Paris Salon exhibition preferred. Instead, they focused on the atmospheric effects of light. They also painted en plein air and bypassed religious, mythological and historical figures to portray ordinary people living their everyday lives.

When trains branched out from Paris, these rebels packed portable easels and paint tubes—both revolutionary inventions for artists—and headed for the coast. Monet gathered with like-minded comrades at La Ferme Saint-Siméon, which overlooks the Seine estuary. The owner, businesswoman Mother Toutain, saw potential in the earnest painters and agreed to accept their works in return for room and board. Saint-Siméon is now a luxury Relais & Chateaux hotel in the enchanting village of Honfleur. With a nod to its former guests, the on-site Impressionists restaurant features palette-shaped tables, and masterworks grace the walls.

Honfleur, the hometown of Impressionist artist Boudin, was spared from major damage during WWII; Photo by rh2010/stock.adobe.com

IMPRESSIVE COLLECTIONS

Honfleur escaped major damage during the war, and the village now appears much as it did in the Middle Ages. Row houses resembling embellished books appear stacked around the quiet inner harbor. Narrow, cobbled lanes fan out from the water, lined with patisseries, bistros and shops. We visited Boudin’s namesake museum and then wandered out to identify his favorite subjects. Born in Honfleur, Boudin rendered his hometown with a loving hand.

In Rouen, with its leaning half-timbered buildings and narrow streets—the same byways likely trod by William the Conqueror, Richard the Lionheart and Joan of Arc—our guide took us to where Picasso captured the old town’s landmark clock. Then, we climbed stairs to the second-story room where Monet painted some of his celebrated cathedral series. At the time, it housed a women’s lingerie boutique, where customers changed in a screened-off area not far from where Monet worked. Instead of focusing on the church’s unusual edifice with three towers in distinctively different styles, Monet obsessed over the way light and weather played off the stonework on the west façade.

The Workshop Lounge at the House and Gardens of Claude Monet in Giverny; Photo by yorgen67/stock.adobe.com

A favorite Norman son, Monet grew up in Le Havre, a city reduced to rubble during air raids in early September 1944. It’s now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, one of the few contemporary designations in Europe. Le Havre’s Andre Malraux Museum of Modern Art acquired two original Monets and contains the world’s largest Boudin collection (bequeathed by the artist).

Monet spent his last 43 years in Giverny, where he planted his famous water lily pond. The painter’s personality shines through his home’s pink- and green-hued exterior, aqua-blue kitchen and radiant yellow dining room. Visitors can purchase combined tickets to the nearby Museum of Impressionism.

The Fisheries Museum in Fécamp; Photo by Shelly Steig

Museums throughout Normandy house an astounding number of Impressionist works. Some of those venues are surprising, such as the Fisheries Museum in Fécamp, a town known worldwide for its Benedictine distillery. I expected a space filled with boats and fish tales. Instead, I found sophisticated exhibitions, including a display of fine art. From the enclosed rooftop, I enjoyed 360-degree views over Fécamp and the Alabaster Coast.

In the majority of museums, art was so accessible that my fingers itched to touch the rough textures. Instead, I leaned in toward Monet’s paintings and peered at the broad, thick strokes that appear as blobs close-up. Then I gradually stepped back until the entire picture came into focus.

Similarly, when I view Normandy as a whole, I see a place and people who embraced beauty, endured an enemy occupation, welcomed bittersweet liberation—and then found beauty once more.