If you enjoy slurping oysters and picking crabs, the Maryland Crab & Oyster Trail serves up a lip-smacking way to tour the state that’s synonymous with Chesapeake Bay blue crabs. The virtual trail lists maritime attractions and more than 100 seafood eateries statewide, but for full-on flavor, head to the areas bordering the Chesapeake Bay.

Crabbing: A Maryland Tradition

Pick a region—Maryland’s Eastern Shore with its eclectic towns and rural stretches, the lively Annapolis area, or Southern Maryland’s colonial towns and tidewater culture—and build your itinerary. Explore fishing villages, climb aboard a waterman’s boat for an interactive cruise, visit a maritime museum, and snap photos of lighthouses and colorful seaside settings.

Of course, you’ll also want to hit up as many seafood joints as you can. Begin your morning with a crab omelet at a mom-and-pop diner; stop at a seafood shack to lunch on fried oysters and hush puppies, those delectable little balls of fried cornmeal; and cap off the day at a waterside restaurant to enjoy a traditional crab feast while watching the sun set.

ON THE WAVES WITH A WATERMAN

Phil Langley’s family goes back four or five generations in Southern Maryland, a long line of watermen and farmers. The jovial, wind-weathered Captain Phil spent much of his life crabbing and oystering commercially. He now operates Fish the Bay Charters in Dameron. Besides guiding fishing charters, Langley is one of numerous individuals, museums and organizations in Maryland offering experiential watermen’s heritage cruises.

With cruise guests aboard the Lisa S, a traditional deadrise workboat built to navigate the shallow waters of the Chesapeake, Langley motors down St. Jerome Creek toward the Chesapeake Bay. He points to a dock surrounded by buoys, the only visible markings of the aquaculture farm of True Chesapeake Oyster Co., one of a growing number of companies farming oysters in the bay.

Langley circles the 1904 Point No Point Lighthouse, calling out various types of seabirds perched on the station once manned by his distant relative, back before the still-working lighthouse was automated.

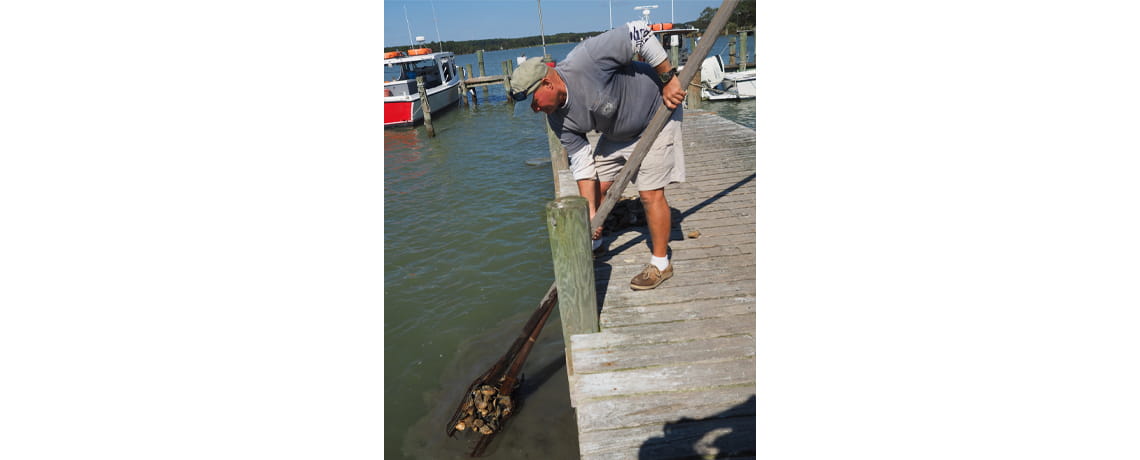

Throughout the three-hour tour, Langley stops repeatedly to pull crab pots, two-foot-square wire cubes baited with menhaden and attached by thick nylon rope to a buoy marked with his unique waterman’s number.

Guests can try hauling out the pots, too. “It’s kind of eye-opening for them when they feel how strong the water pressure is; it’s not as easy as they think,” he says. “It’s a lot of physical work involved, especially if you’re crabbing or oystering full time, and there’s no guarantees.”

In the early 1980s when Langley began his career, he would set 150 pots, pull them all by hand (a process now typically done hydraulically), and end up with about 10 to 12 bushels of crabs in a day. “Not anymore,” he says. With pollution and past overharvesting, there are simply fewer crabs in the bay. “Now you need to set at least 300 pots to get that kind of harvest. Some guys set 500 to 800 pots just to survive,” he says.

To help the bay rebound, Maryland has strict regulations for commercial crabbing, mandating the season, hours on the water, gear, catch limits and crab size. If the crab is too small, it must be returned to the water.

Later, back ashore, the crabs are steaming over an open fire and Langley spreads thick brown paper on tables under a waterfront pavilion. When the now bright-red crabs are ready, he brings them to the tables, proffering a big tin of Old Bay seasoning.

He gives a demo in crab picking for any novices in the group. First, remove the claws and legs. Then, remove each of the back fins by cracking them at the joint to get at that jumbo lump backfin, the most succulent meat in the body.

Next, pry open the apron (located on the underside), and snap it off. Pull off the top shell as well. Remove the exposed gills and, if you’re not a fan, the yellow-green mustard (the equivalent of a liver). Break the crab body into quarters, exposing the small bits of meat to pick out with your fingers, your knife or a small fork.

Finally, crack each of the claws with a mallet or nutcracker, and pull out the hunk of sweet claw meat, ready-made to dip in butter.

Repeat, again and again.

Crab picking is deliciously messy business, and it takes time. Most people will eat a dozen or more crabs, so settle back for a long, sociable meal.

REVIVING THE BAY'S OYSTER REEFS

As with crabs, the number of oysters in the bay has dwindled over the years because of overharvesting, disease and habitat loss. The native Eastern oyster population is now just 1 percent of historic levels, according to the Chesapeake Bay Program.

That’s not only bad news for those of us who enjoy eating oysters. The bivalve is essential to the health of the bay itself: filter-feeding oysters clean the water, and oyster reefs provide habitat for other marine life.

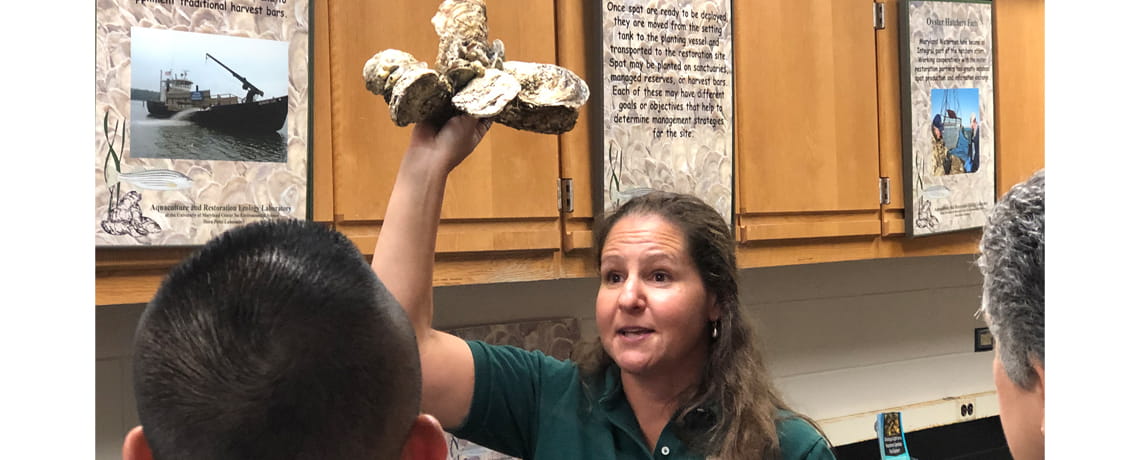

The good news is that a host of governmental, research and nonprofit organizations are working to restore the bay’s oyster population. You can get a behind-the-scenes look at the Horn Point Oyster Hatchery in Cambridge and at the visitor center of the Chesapeake Biological Laboratory in Solomons, both run by the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. (Call before visiting, as the pandemic has affected public access.)

If you want to get your hands dirty while learning about oysters, you can volunteer at the Maryland Oyster Restoration Program operated by the nonprofit Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF). (Although oyster-focused, it’s not part of the trail.) The program’s facility is about a 35-minute drive south from Annapolis at a working waterfront in Shady Side.

“It’s not a fancy-schmancy place,” admits Doug Myers, a Maryland senior scientist with CBF. “Everything here has been soaked in saltwater for 20 years. It’s a very hot, sweaty, mos quitoey kind of place in the summer.”

But it’s here that employees and volunteers recycle oyster shells (1,100 bushels of them in 2019) and seed them with larvae to produce new oysters. The baby oysters, called spat, are then deposited in artificially created reefs in protected areas.

None of the nearly 8 million spat produced and planted in 2019 will end up on your plate, but they are vital to life in the bay.

“For so many people, all they know about oysters is they’re on the half shell when you eat them,” Myers says. “But there are up to 300 species associated with an oyster reef, including sport fish like black sea bass and red drum. Without the oyster reefs, those fish wouldn’t be in the bay.”

MUSEUM AND A MEAL

For a laid-back nautical-themed day, combine a visit to one of more than a dozen maritime museums in the state with a seafood meal at one of the trail restaurants.

ANNAPOLIS HAVRE DE GRACE ST. MICHAELS SMITH ISLAND SOLOMONS

ANNAPOLIS

Maryland’s capital city is a favorite for many tourists who love its well-preserved buildings showcasing centuries of architectural styles as well as its vibrant waterfront and downtown, filled with shops and restaurants. Those who have yet to visit the Annapolis Maritime Museum & Park—or haven’t done so recently—are in for a treat. The 20-year-old museum, housed in a former McNasby Oyster Company packing facility, received an overhaul in 2020.

Now, a speaking holographic waterman greets visitors to the 2,500-square-foot museum with high-tech interactive exhibits highlighting three themes: Annapolis Waters, Bay Health and Oyster Economy. Peer into two 500-gallon aquariums that contrast life in the bay in the early 1600s with that of today. Sitting in a small boat, choose one of three virtual reality experiences.

Just outside the museum, you can board the historic skipjack Wilma Lee for a heritage, lighthouse or sunset sail or to watch the Wednesday Night Sailboat Races, which typically run from the end of April to Labor Day. Across Back Creek from the McNasby museum building is the museum’s park, where you can rent kayaks or standup paddle boards from Capital SUP or embark on guided kayak tours of the waterways on Sundays.

America’s Sailing Capital has an abundance of restaurants that serve fresh local seafood. It doesn’t get any fresher than the fare at Wild Country Seafood, located just behind the maritime museum. The old-school crab shack is owned by watermen Pat Mahoney Sr. and Jr. Order up a meal of locally caught rockfish, perch, oysters or crabs or Mahoney’s own brand of aquaculture oysters—Patty’s Fatty’s—to eat at the on-site picnic tables or take home.

A favorite gathering spot for local sailors, the Boatyard Bar & Grill has a bountiful raw bar serving up oysters on the half shell as well as oyster shooters, clams, mussels and shrimp. The Boatyard’s “all killer, no filler” crab cakes are award-winning.

For a more formal setting, choose the waterfront Carrol’s Creek Café, with seating indoors and out. Start with the scallops appetizer, a menu favorite for 36 years running. Carrol’s rolls the sea scallops in shredded phyllo, fries them to a crisp, and serves them on a bed of wilted spinach, lump crab and prosciutto, all topped with a shrimp cream sauce. Try crab soup one of two ways: tomato-based Maryland vegetable crab or rich cream of crab. Follow up with local rockfish or jumbo lump crab cakes. visitannapolis.org

HAVRE DE GRACE

Nestled at the head of the Chesapeake, where the Susquehanna River flows into the bay, Havre de Grace attracts day-trippers and weekenders looking for a dose of bay culture and some good eating. The 1827 Concord Point Lighthouse and Keeper’s House, typically open for tours on weekends April through October, anchors one end of the town’s grassy waterfront promenade, which also features a boardwalk.

Havre de Grace has not one but two museums treating life on the northern bay, and both are located on the waterfront. Hunting waterfowl has long been part of Upper Chesapeake Bay heritage. Over the years, the once-rough-hewn utilitarian representations of waterfowl used by hunters evolved to finely sculpted and intricately painted works of art. You can view both types at the Havre de Grace Decoy Museum, which boasts one of the finest collections of Chesapeake Bay decoys in existence.

The Havre de Grace Maritime Museum & Environmental Center feature exhibits on a host of bay-related topics, from shipbuilding and working on the bay to boat racing and other forms of recreation.

When it’s time to chow down, you’ll find two restaurants in Havre de Grace on the Maryland Crab & Oyster Trail: The Bayou and Water Street Seafood. The Bayou has been a local favorite since 1949. The restaurant doesn’t have outdoor seating or a view, but its menu features a boatload of seafood options for every course. Well, okay, not for dessert, but for appetizers, soups, sandwiches and entrées. (Be sure to check the website for current operating hours.)

While Water Street Seafood may be a relative newcomer in town (it opened in January 2020), it occupies the waterfront building that was home to the iconic Price’s Seafood, and the new owners are every bit as serious about serving up the best steamed crabs. That means Chesapeake Bay crabs late spring through fall and North Carolina or Louisiana crabs in winter. There’s a raw bar, too, and a long list of seafood options is available baked, broiled, fried, or in a soup or stew. explorehavredegrace.com, visitharford.com

ST. MICHAELS

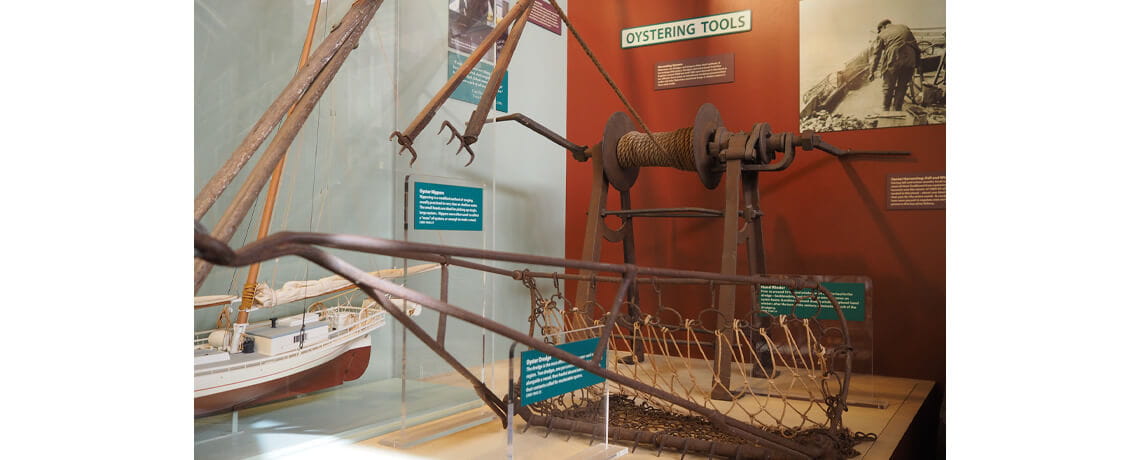

Marinalife magazine ranks the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum in the popular Eastern Shore town of St. Michaels among the nation’s Top 10 Maritime Museums. Little wonder: The 18-acre waterfront campus boasts 12 buildings with exhibitions about life, work and play on the Chesapeake.

Wannabe watermen can pull a crab pot and tong for oysters at the re-created crabber’s shanty, watch shipwrights at work in the boatyard, and cruise aboard the Winnie Estelle, a restored 1920 buyboat (used by a middleman who would buy the day’s catch from watermen on the bay and sell it to dockside customers).

Visitors can play at lighthouse-keeping in the hands-on exhibit inside the 1879 Hooper Strait Lighthouse that once stood in Tangier Sound, warning of the dangerous shoals at Hooper’s Strait. Another prized museum building is the Mitchell House, once the home of Eliza Bailey Mitchell, sister of abolitionist Frederick Douglass. The 19th-century St. Michaels structure houses an exhibition about the life of free African American laborers who once made up a third of the watermen on the bay.

After your museum visit, walk next door to The Crab Claw, a fixture in town for more than 50 years. It’s open spring through fall, so get a picnic table on the deck overlooking the Miles River, and order up a proper Chesapeake Bay feast: oysters on the half shell, rockfish and steamed blue crabs liberally dusted with Old Bay seasoning.

The founder of the Awful Arthur’s seafood restaurant chain, Arthur Webb Jr. comes from a long line of watermen. He no longer owns the chain, but he’s reserved one very special Awful Arthur’s location as his favorite: the one in St. Michaels. Tucked in the heart of downtown, the restaurant is renowned for its Oyster Bar, which includes at least nine varieties of oysters on the half shell. There’s an expansive outdoor seating area with heaters and fire pits, too.

The place for an extra-special meal is STARS at the Inn at Perry Cabin, which also boasts the most elegant accommodations in town. Executive Chef Gregory James oversees a farm-to-table (and bay-to-table) menu that changes as the local bounty does. You’re here for the seafood, of course, so look for stellar options such as meaty Chesapeake Bay crab cakes and oysters served roasted or on the half shell. The oysters are farmed just eight miles away at Harris Creek Oyster Co.

STARS’ oyster pièce de resistance is its oyster stew, the reigning champ in Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum’s OysterFest competition. The light milk-based dish gets its appealing—and unique—taste from lemongrass and ginger.

Diners have spectacular views of the Miles River from inside STARS and from the patio in warmer months. In response to COVID-19, the inn also added four temperature-controlled glass houses for waterside private dining for up to four people. Closed in the coldest winter months, they will reopen as soon as temperatures permit.

SMITH ISLAND

English and Welsh settlers arrived on this nine-square-mile Chesapeake Bay island in the 1600s, yet more than 350 years later, Smith Island remains a place apart. Officially in Somerset County, 12 miles away on the Eastern Shore, it is the only inhabited island in Maryland that must be accessed by boat.

Just about 150 people live there year-round, down from a high of 800 in the early 1900s. Most are descendants of those early settlers, and they retain an accent and dialect reminiscent of Cornwall, England. In 1872, the Reverend James Massey described the island’s inhabitants as “an amphibious race,” and the moniker remains apt. The vast majority of Smith Islanders earn their living fishing, crabbing and oystering.

There are houses available to rent as well as a few bed-and-breakfasts, but most tourists come for a half-day trip. Cruise boats operate from summer to early fall from Lookout Point State Park in Southern Maryland and Crisfield on the Eastern Shore.

It’s a short walk from the wharf in Ewell, the island’s largest town, to the Smith Island Cultural Center & Museum. A well-done film by the Maryland Historic Trust introduces visitors to Smith Island, and museum exhibits focus on island history and culture, traditional watercraft and crabbing. Golf carts can be rented for a jaunt around Ewell.

Smith Island is noted for its crab cakes, softshell crabs and Smith Island cake, the state dessert. You can get all three at Bayside Inn & Restaurant, located near the wharf. Lovers of the 8- to 10-layer cake can pick up a half or whole cake from Bayside Inn or from Smith Island Bakery, but you’ll need to order your cake in advance from the bakery. visitsomerset.com

SOLOMONS

The Calvert Marine Museum focuses on the ecology of tidewater Maryland and history of those who have made their lives and their living on the water—from Algonquin-speaking people of 12,000 years ago to today’s watermen and recreational boaters. The 20 or so tanks in the Estuarine Biology gallery are home to species that live in the bay and its tributaries: oysters and blue crabs, but also turtles, snakes, seahorses and a variety of fish, including the chain dogfish, a type of small shark.

Three resident river otters (an oyster-loving species) have an indoor/outdoor habitat where they entertain with their antics, while the quarter-mile Marsh Walk provides a close-up view at low tide of birds, crabs, fish and plant life. If it’s open, tour the furnished 19th-century Drum Point Lighthouse, too.

During the summer, the museum offers sightseeing cruises on the 1899 Wm. B. Tennison, a log-built bugeye workboat, as well as two-hour sails on the historic skipjack Dee of St. Mary’s.

A short distance away in Solomons Island lies a museum treasure: the National Historic Landmark Lore Oyster House. While the building awaits repair from flood damage, visitors can peek through the dusty windows and imagine the mainly African American men and women who day after day performed the monotonous, hand-crippling work of shucking, sorting and packing oysters.

Afterward, stroll the picturesque stretch bounded on one side by Back Creek and on the other by the Patuxent River. Pick one of the restaurants with an enviable view. The Lighthouse Restaurant & Dock Bar, for example, serves up local seafood and ogle-worthy views of the many docks on Back Creek. For optimal sunset views of the Thomas Johnson Bridge that spans the Patuxent River, choose The Pier Restaurant, built out over the river and offering tables next to floor-to-ceiling windows and on the deck. choosecalvert.com

FESTIVALS AND FEASTS

When it’s again safe to gather in large groups, you can be sure we’ll see the return of the state’s many seafood-centric celebrations. The community gatherings take place spring through fall, from the Great Havre de Grace Oyster Feast at the bay’s northern end to the St. Mary’s County Crab Festival in Southern Maryland.

Chesapeake Bay blue crab season kicks off in April, making this the perfect time to plot your course on the Maryland Crab & Oyster Trail (visitmaryland.org/article/maryland-crab-oyster-trail).