“When people tell me nothing has changed, I say come walk in my shoes and I will show you change.”

- US Congressman John Lewis

I grew up in Michigan in the 1970s, and I remember my father always saying how much he preferred the South because there the racism was overt and he knew the boundaries he could and could not cross.

When a first-grade white classmate called me the n-word, I ran home confused and angry to ask my father about the meaning of that word. That’s when my dad introduced me to Jim Crow and the civil rights movement. My father was a member of the Urban League, and his father, my granddad whom I called “Bompie,” was a lifetime member of the NAACP, so I heard a lot about Jim Crow through the years. When I was young, I thought that Jim Crow was an old, nasty field bird that a scarecrow could frighten away. To this day, I still picture an old ragged bird when I hear that term.

The stories my dad and Bompie shared, however, didn’t prepare me for the emotional journey I would take when visiting sites along the United States Civil Rights Trail. I grew up with a lot of love, so the level of hate I’ve learned about through the exhibits and stories on the trail is beyond disturbing.

Created in 2018, the United States Civil Rights Trail plays an important part in preserving and sharing the history of one of the most transformative times in America’s story. With 100-plus stops across 15 states, predominately in the South, the trail is expansive, and it continues to grow because there are traces of civil rights history in every US state.

I travel a lot, and on different trips throughout the country, I’ve visited Civil Rights Trail sites in Florida, Louisiana, Missouri and Delaware. Until I began visiting those sites, I didn’t understand fully the impact that the civil rights movement had had on my life. As a Black woman in her 40s, I had never experienced a Jim Crow South, but I have and continue to experience racism.

Viewed through the lens of the current Black Lives Matter movement, it might appear that not much has changed in our country since the 1950s and 1960s. I, too, have questioned what progress has been made. But as the late US Congressman John Lewis suggested, we should walk in his shoes to see what has changed.

The Civil Rights Trail allows us to figuratively step into the shoes of Lewis and others who paved the way for the first Black man to become President of the United States and the first Black woman to be nominated as Vice President on a major political party ticket. These are significant achievements, but the work for civil rights is far from over.

From my experience, every single lesson or story that a Civil Rights Trail site provides is informative and impactful. But the sites I’ve visited in Birmingham, Alabama, have been the most memorable.

Birmingham Civil Rights Institute. Photo by Ted Tuker

RISE OF A MOVEMENT

Birmingham played a significant role in the civil rights movement, but the September 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church proved a turning point in the movement. The explosion killed four young Black girls who were attending Sunday school. The church was targeted because it was it was an organizing site for civil rights protests.

It broke my heart to look down at the simple black plaque marking the spot where the bomb was planted. Four red carnations ornament the plaque, one placed above each of the four girls’ names: Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Denise McNair and Carole Robertson. Beneath their names is etched the date and exact time of the deadly blast: 10:22 a.m., September 15, 1963.

The hateful act was the Ku Klux Klan’s response to Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech 18 days earlier. My eyes watered and I became enraged when I learned that minutes before their deaths, these innocent souls heard a Sunday school lesson titled “A Love That Forgives.” I found myself asking whether love really can forgive this degree of hatred.

The Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, a Smithsonian Affiliate, is a cultural and educational research center that greets visitors with an array of greenery lining the staircase leading to the domed rotunda entrance. The natural light that floods the rotunda is a sharp contrast to the sometimes dimly lit exhibit areas. Against the lower lighting in the first room, a spotlight features a Klan robe and hood in a glass encasement. The sight of it made me nauseous and angry.

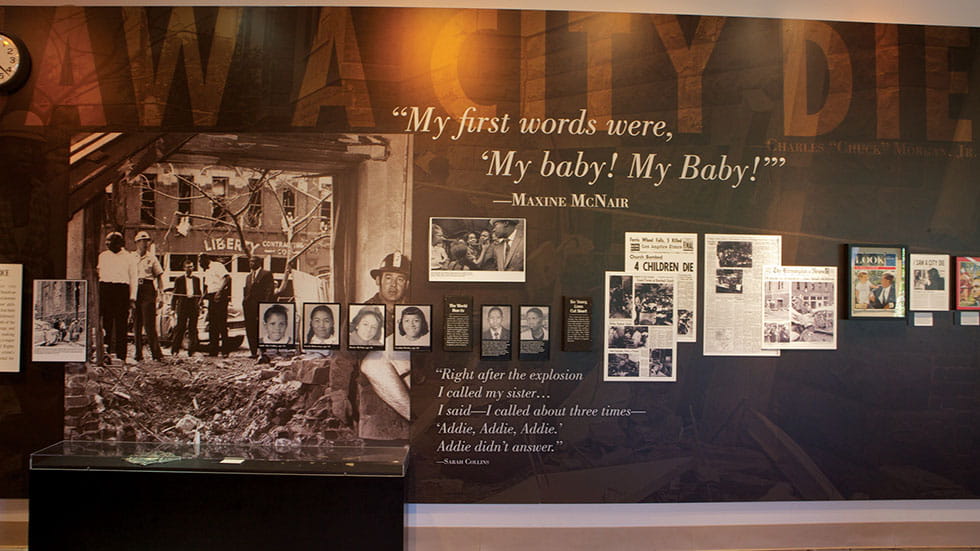

“Right after the explosion, I called my sister… Addie Addie Addie Addie didn’t answer…” Historical accounts of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing exhibited at the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute. Courtesy Of Greater Birmingham Convention And Visitors Bureau

The Institute houses many artifacts, including the door from the jail cell in which King was being held when he wrote his famous “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” There are recreations of settings from the 1950s, including a lunch counter, a cinema lobby and two distinctly different classrooms: a classroom for Black children with minimal and worn supplies and a classroom for white children with modern equipment, proper lighting, freshly painted walls and a fan.

Across from the Institute is Kelly Ingram Park, a four-acre public park that had been the staging area for many student demonstrations in Birmingham led by King, Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth and others. In 1992, the park was transformed into a sculpture garden and rededicated as “A Place of Revolution and Reconciliation” to coincide with the opening of the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute.

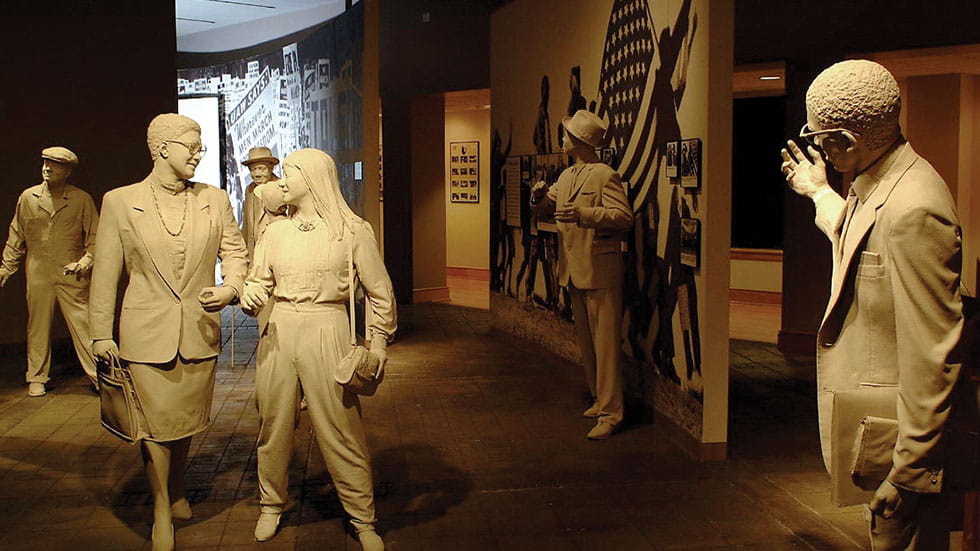

The beautifully crafted sculptures portray emotionally charged stories about the fight for civil rights. As I traveled the sidewalk path named Freedom Walk, I stopped at a metal sculpture by Ronald McDowell that pays tribute to the foot soldiers in the Birmingham movement. That sculpture, based on a famous news photo, shows a policeman who is holding a Black teenage boy in one hand and a fiercely growling police dog in the other hand. The artistry is so detailed that it caused me to hold my breath when I looked into the angry dog’s eyes and saw the fear and anguish in the boy’s face as he braced for an attack.

Historical accounts of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing exhibited at the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute. Courtesy Of Greater Birmingham Convention And Visitors Bureau

All along the Civil Rights Trail, the sites illuminate the story of the civil rights struggles. Some, such as those in Birmingham, focus on a city’s or state’s stories, while others, including the Rosa Parks Museum in Montgomery, Alabama, and The King Center in Atlanta, Georgia, pay tribute to iconic civil rights actors. Each site on the trail—from the Deep South to my hometown of Washington, DC—provides a piece of the civil rights story and displays snapshots of courage.

One of my favorite snapshots is at a site I visit often: the Lincoln Memorial. Just below the top landing, the marble floor is inscribed to commemorate where King stood when he gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech at the August 28, 1963, March on Washington. When I stand in the very spot where MLK stood, and look out over the National Mall, visualizing the energy of that day my breath away.

I have my dad and Bompie to thank for my love of history. The stories I’ve heard about the brave civil rights fighters—including my dad’s college friend Ernest Green, one of the Little Rock Nine who enrolled at the formerly all-white Little Rock (Arkansas) High School—have left an indelible impression on me. I often wonder what my dad and Bompie would say about today’s Black Lives Matter movement. I can almost hear their voices complaining about the systemic racism we’re seeing today. I can certainly hear their voices through the familiar stories I’ve heard along the Civil Rights Trail. Sometimes it seems as if my dad and Bompie are walking right alongside me, whispering in my ear. Learn more at civilrightstrail.com.

Tonya Fitzpatrick at the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial in Washington, DC. Photo by Blair Caldwell

A NATIONAL MONUMENT TO CIVIL RIGHTS

Three of the four Birmingham sites on the United States Civil Rights Trail—Bethel Baptist Church, 16th Street Baptist Church and Kelly Ingraham Park—are also part of a larger grouping of sites that make up the Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument, created in January 2017 by President Barack Obama shortly before he left office.

Once it is restored, the A.G. Gaston Motel will be the centerpiece of the roughly four-block national monument in downtown Birmingham. The Black-owned motel had served as headquarters for the Birmingham civil rights campaign when Martin Luther King Jr. and other leaders of the movement took up residence here in April and May 1963. The motel is next to the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute.

Also part of the national monument are St. Paul United Methodist Church, a departure point for the April 1963 Palm Sunday Children’s March, and the 4th Avenue Historic District sites, which are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The District was the retail and entertainment center for Black-owned businesses that served African American customers during forced segregation.

You can read more history and learn about the national monument at nps.gov/bicr.