Mammoth Cave. Photos courtesy of NPS

MAMMOTH CAVE NATIONAL PARK

Kentucky

This World Heritage Site in west-central Kentucky is the world’s longest cave system, winding beneath lush forests and fish-filled streams for nearly 300 miles. Its complex network of cave formations—chambers, shafts, and delicate gypsum “flowers” and “needles”—displays a greater variety of sulfate minerals, including mirabilite, epsomite and celestine, than any other place on (or under) the earth.

Need more superlatives? According to UNESCO, the cave features the world’s richest assemblage of underground wilderness, including 14 species of subterranean critters—troglobites (such as crustaceans) and troglophiles (frogs, salamanders)—that can be found only here.

Choose from several guided tours, when available, or venture into the cave system on your own, beginning and ending at the historic entrance, a natural opening that’s been used for some 5,000 years. Highlights include landmarks such as a historic saltpeter mining site and a 40-foot-long boulder known as Giant’s Coffin. You’ll likely encounter a bat or two in the dark passageways, of course. Above ground, another 45 animal species, from white-tailed deer to mink to bobcats, roam the nearly 53,000-acre park.

Jewel Cave. Photos courtesy of NPS

JEWEL CAVE NATIONAL MONUMENT

South Dakota

nps.gov/jeca

This gem of a cave—at 208 miles, the world’s third longest—gets its name from the ruby- and amber-hued crystalline calcite spars that glitter everywhere you turn. Stalactites are relatively rare here; instead, you’ll see plenty of other types of speleothems, including the sheet-like decorative flowstone, milky soda-straws (hollow tubes) and popcorn, often a cave-hunter’s favorite. Nestled beneath the iconic Black Hills of South Dakota, in the southeastern corner of the state, the cave remains relatively intact and unchanged, according to the National Park Service, and the great bulk of it has yet to be explored. Nine bat species call this dark underworld their home, including the Northern long-eared bat, which has been designated as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act.

There are no self-guided tours here, and visitors must be accompanied by a ranger at all times; experiences range from Historic Lantern Tours to wild caving tours. While cave tours have been suspended since December 2020 for construction at press time, they were expected to resume in mid-June.

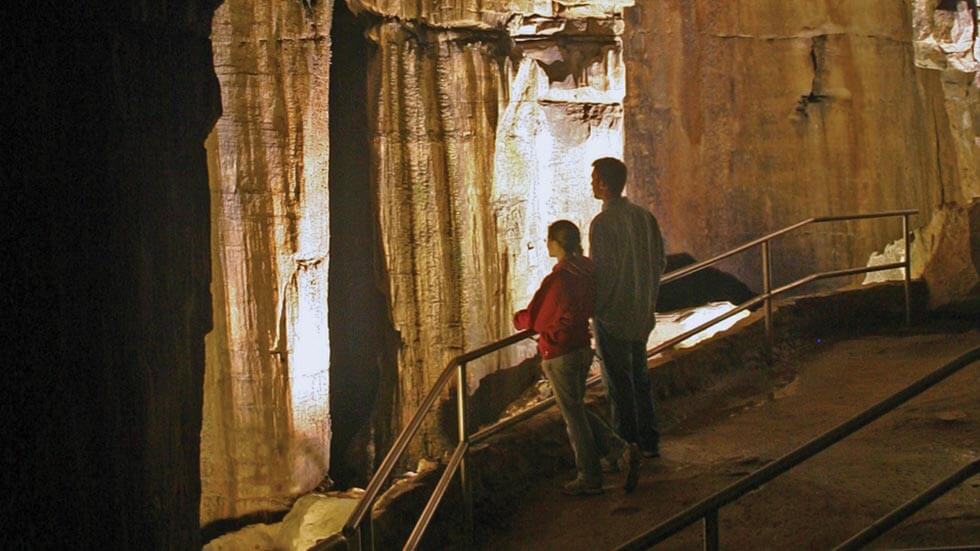

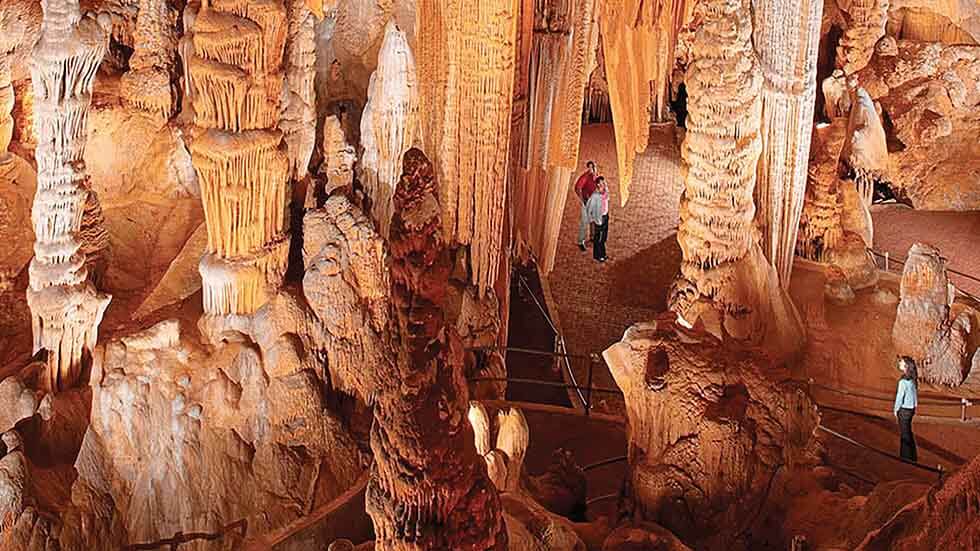

Luray Cavern. Photo by dan austin/nps. courtesy of nps

LURAY CAVERNS

Virginia

luraycaverns.com

At three-and-a-half acres, this trove in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley is the largest cave system in the Eastern US, a natural landmark that bills itself as the “geology hall of fame.” Distinguishing features include a multitude of naturally sculpted stone columns. Be on the lookout for one in particular: a spectacular 47-foot-high example that’s the result of a merger of two classic cave formulations, a stalagmite (rising from the floor) and stalactite (hanging from the ceiling).

Elsewhere in the caverns, you can marvel at brilliantly white, chandelier-like creations of limestone that pour to the ground like waterfalls as well as a cool reflecting lake whose shimmering depth appears to dive straight to the earth’s core, yet is less than two feet deep.

Most visitors spend about 1 hour and 15 minutes taking the self-guided tour, and staff members stationed throughout the caverns can answer questions.

If these organic structures aren’t enough, there’s one more—manmade—intervention that’s bound to set your heart pounding. It’s the Great Stalacpipe Organ, deemed by none other than Guinness World Records as the world’s largest musical instrument. Instead of blowing air through pipes, this contraption—designed by a mathematician in the 1950s, it’s actually something called a lithopone—strikes 37 variously pitched stalactites scattered throughout 3.5 acres of the cave, creating melodies that can be heard throughout the 64-acre cavern. Now, that’s different.