Pandemic grief nearly undid Duncan Phillips. The Washingtonian and his mother, Eliza, were still mourning the death of family patriarch Major Duncan Phillips from a heart condition when the deadly virus ravaging the nation struck down Duncan’s beloved older brother, Jim, at the age of 34.

The two brothers had been extremely close, attending college together and later sharing an apartment in New York City. Duncan struggled to cope with his loss, later recalling, “Sorrow all but overwhelmed me.”

Long passionate about the visual arts, it was in art that Duncan found salvation. “I turned to my love of painting for the will to live,” he explained. And when he wanted to memorialize his loved ones, he did so through art.

And so it was that in 1921, Duncan; his new wife, artist Majorie Acker; and Duncan’s mother created a gallery on the second floor of the family’s home in DC’s Dupont Circle and invited the public to view works from their nascent collection of 273 paintings. Phillips was determined that the gallery have “a joy-giving, life-enhancing influence” and be “a beneficent force in the community.”

The museum they birthed is The Phillips Collection, known as America’s first museum of modern art and noted for owning one of world’s most important collections of American art.

Since its founding 100 years ago, the museum’s collection has grown to 6,000 pieces, and its exhibit space has likewise grown exponentially—to 60,000 square feet—overtaking the Phillips’ home within a decade and since expanding into two major additions.

HEALING THROUGH ART

The timing of the centennial of The Phillips was lost on no one.

Planning for the anniversary had begun in 2018, and momentum was growing rapidly when the COVID-19 pandemic hit. The group of 13 community members selected to help shape the centennial exhibition held its first meeting on March 6, 2020; within a week, the city had closed down, notes Elsa Smithgall, curator of Seeing Differently: The Phillips Collects for a New Century.

“The coincidence of the two pandemics and then the confrontation with social and racial inequity that came violently to the forefront as we were planning our centennial, I think all of that changed the orientation in an important way,” says Dorothy Kosinski, director and CEO of The Phillips Collection.

Aparna Sadananda guides a meditation inspired by Regina Pilawuk Wilson's Sun Matt (2015) during the Phillips' 2018 exhibition Marking the Infinite: Contemporary Women Artists from Aboriginal Australia. Photo by Rhiannon Newman

“As an institution, [our centennial observation] is not all about us,” she says. “Instead, we asked, ‘What can we do? How can we help? How can we be forward-thinking and a force for good in society? That certainly is consonant with what Duncan wanted to accomplish.”

It’s not that The Phillips was not already invested in the community and in carrying out Duncan’s vision. For years, the museum has worked with teachers and students, veterans, the elderly and Alzheimer patients. Meditation sessions were held regularly in the galleries, and the museum has a series of contemplative audio tours. The Phillips’ satellite campus at the Town Hall Education and Recreation Campus (THEARC) in Southeast DC offers free art-making sessions and exhibits community members’ art.

But the need to use art to heal had suddenly become more urgent.

The centennial exhibition’s title Seeing Differently had been selected early on, Smithgall notes, “but I have to say, it took on an even more profound meaning in the face of the past year and what we’ve all experienced.”

COLLECTING WITH CONVICTION

Many people think of The Phillips Collection as a place to see French Impressionist art, and it does, indeed, have an enviable collection of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist works by the likes of Claude Monet, Edgar Degas and Vincent van Gogh. Its best-known work is undoubtedly Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Luncheon of the Boating Party.

Fewer people realize that Duncan was in many ways a pioneering collector. He was avidly purchasing French moderns (including Pierre Bonnard and Henri Matisse) in the 1920s, well ahead of other American museums, and was an early proponent of Pablo Picasso.

Georgia O'Keeffe's Large Dark Red Leaves on White, 1925, oil on canvas, 32 x 21 in., The Phillips Collection, acquired 1943; ©2021 The Georgia O'Keeffe Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

He was also unafraid to purchase little-known artists. The Phillips became the first museum to collect works by Arthur Dove, Georgia O’Keeffe and Grandma Moses and to launch solo exhibitions of Marc Chagall and Henry Moore.

Duncan frequently bought and exhibited works by regional artists, many of whom went on to become famous. Among them was painter and art historian David Driskell, one of the world’s leading authorities on African American art and a former member of the museum’s board. Driskell died of the novel coronavirus in April 2020.

CREATIVE WAYS OF EXHIBITING

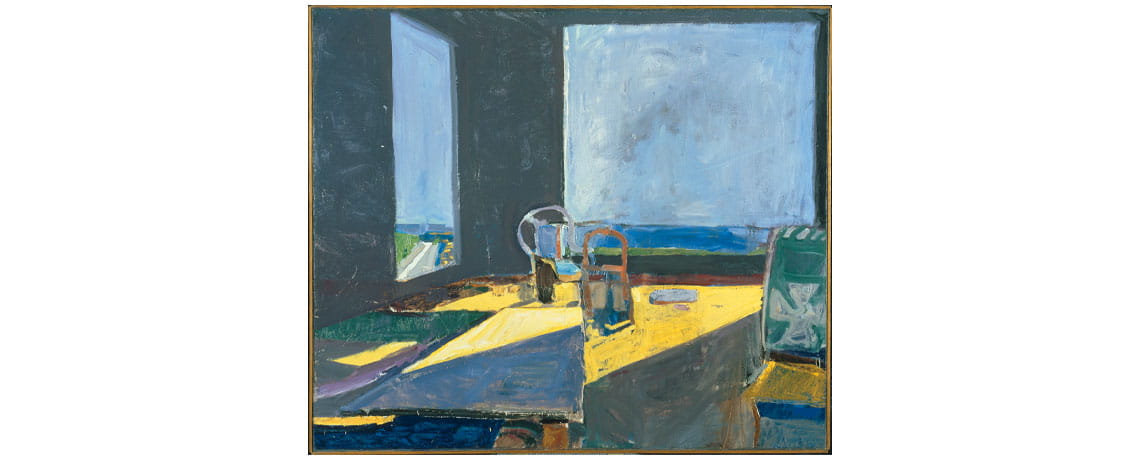

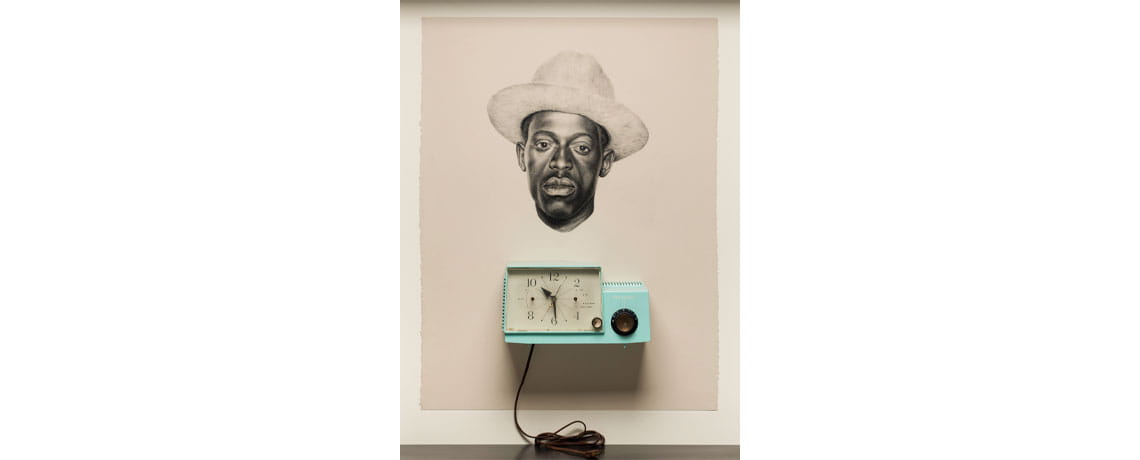

From the outset, Duncan had envisioned The Phillips as “an intimate museum combined with an experiment station.” Along with his pioneering purchases, he departed from museum norms in the way he exhibited art, showing side by side works from different periods, different genres and different media.

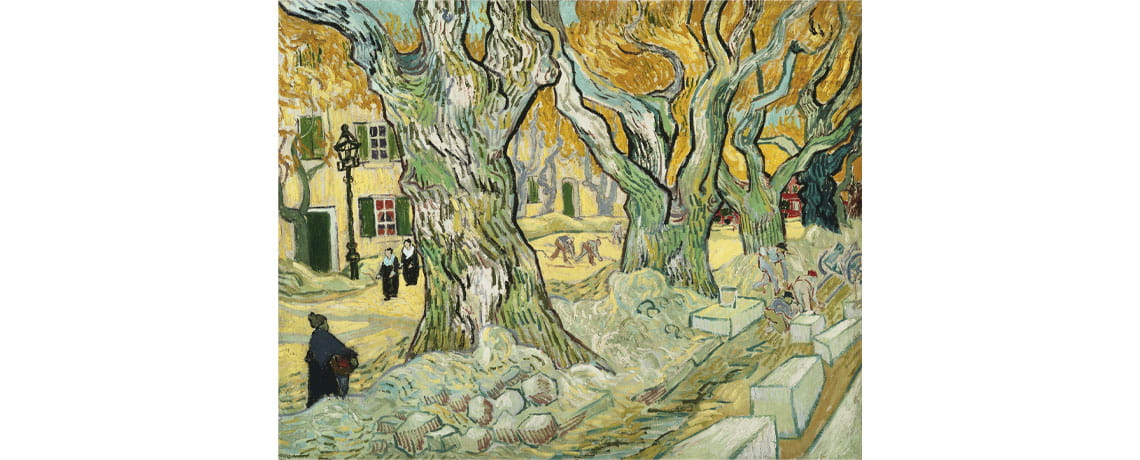

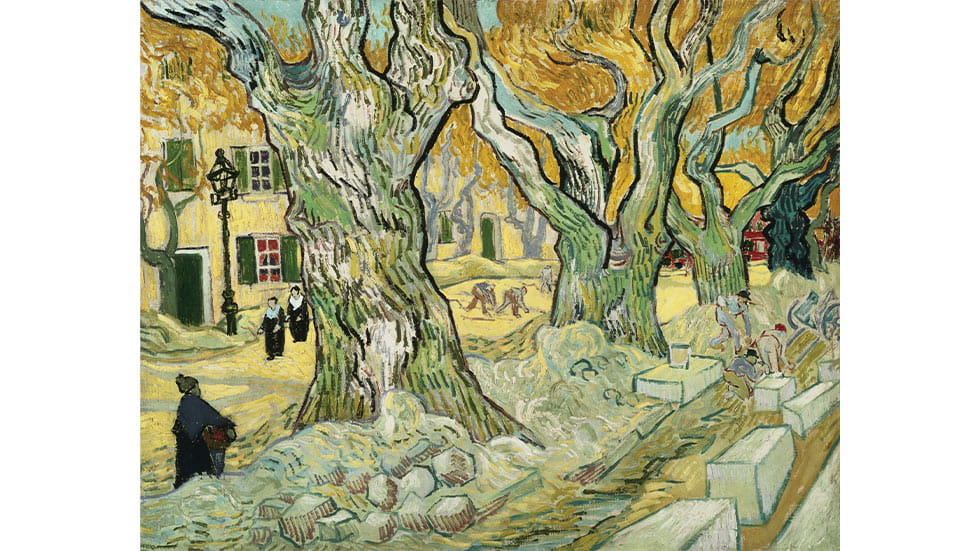

Vincent van Gogh's The Road Menders, 1889, oil on canvas, 29 x 36 1/2 in., The Phillips Collection, acquired 1949

“Even 20, 30 years ago, almost all museums had very strict ways of exhibiting art, mostly historically. So, you would have a room for 19th-century Impressionism, a room for 20th-century Modern, a room for American art and so on,” says museum curator Klaus Ottmann. “Duncan would never do that. He believed that it was extremely important to create conversations between the old and the new, between different periods, different mediums, different artists.”

The museum continues to exhibit this way, and since artworks rotate frequently, Ottmann says, “We always have new juxtapositions, new conversations—and what that does is it creates new layers of meaning over and over.”

NEW WAYS OF SEEING

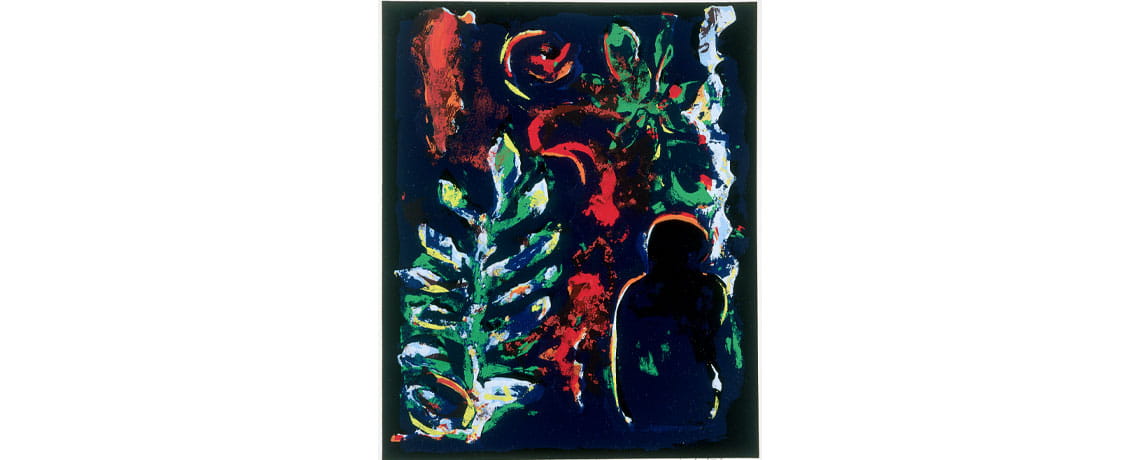

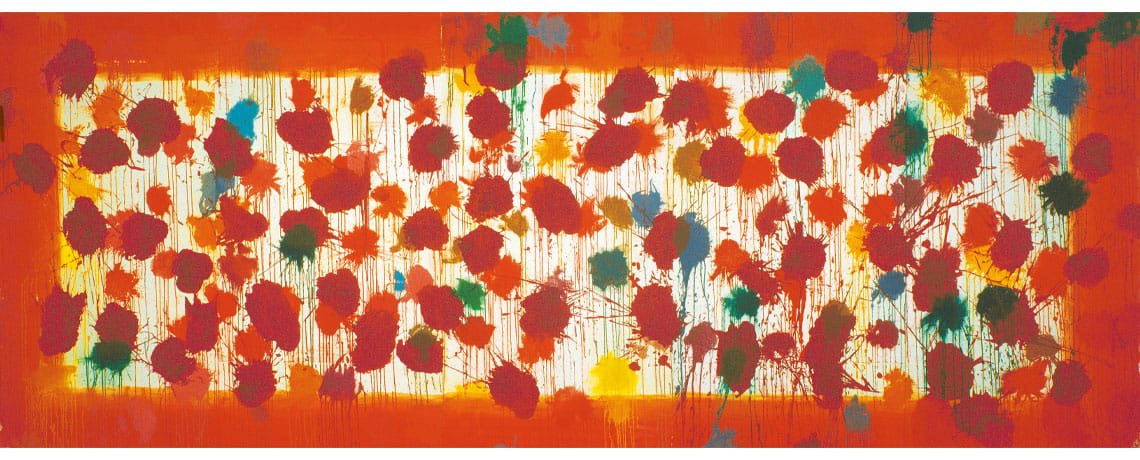

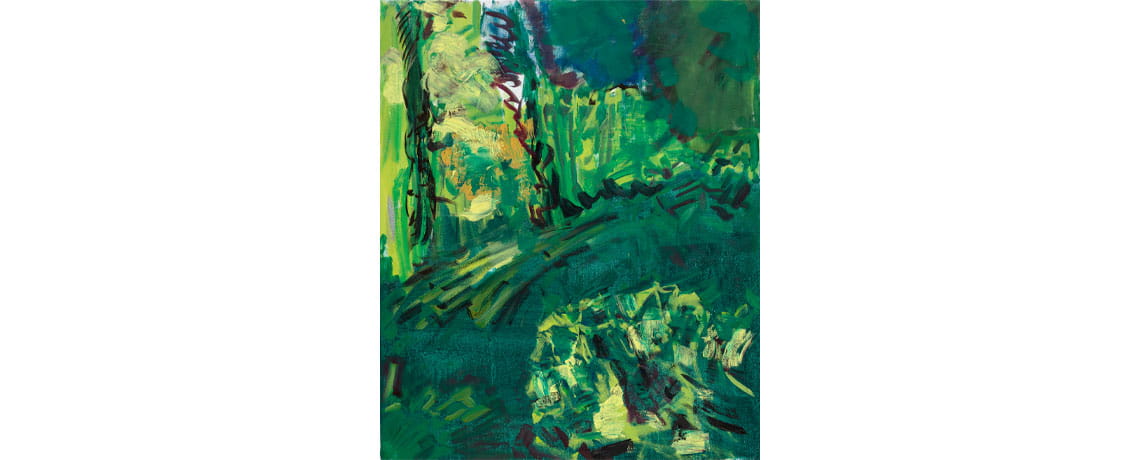

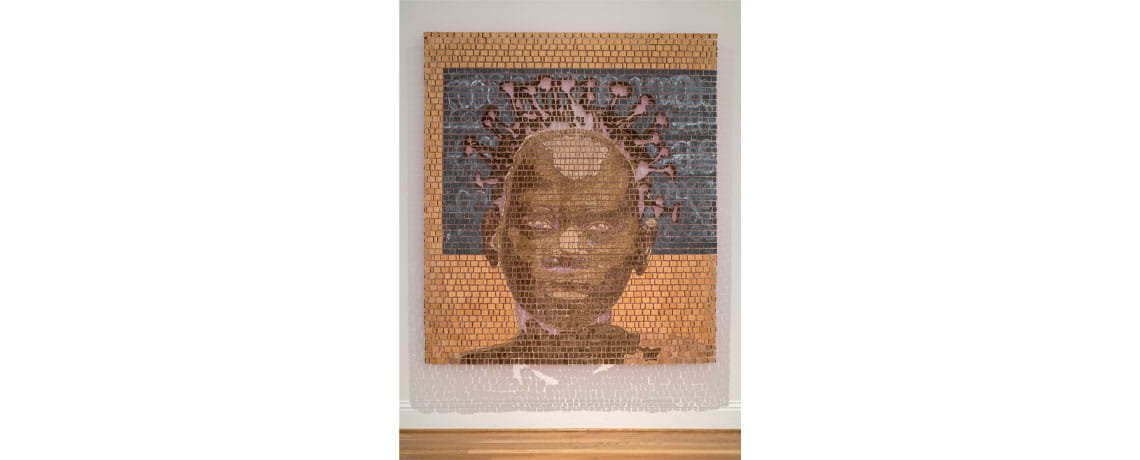

That approach is especially evident—and valuable—in Seeing Differently, which runs through September 12. The more than 250 works in the centennial exhibition represent a diverse array of artists from around the world and include paintings, drawings, sculptures, videography and photography. Dates of creation range from the early 1600s, with El Greco’s The Repentant St. Peter, an emotion-rich portrait in a style recalling Byzantine iconography, to 2020, with Federico Solmi’s The Great Farce: Portable Theater, a vibrantly colored satirical mixed-media vision of modern society as a dystopia.

Seeing Differently embraces “the overarching idea of our ever-changing world,” Smithgall says, with works grouped into four themes—identity, the senses, history and place—and divided further into topics showcasing a range of artistic responses.

The history-themed section, for example, features artworks inspired by wars (the French Revolution, the US Civil War, World Wars I and II); by slavery and its aftermath (including numerous panels from Jacob Lawrence’s seminal work The Migration Series documenting the post-World War I migration of Blacks from the rural South to the urban North); and by migrations, displacements and exile (such as Joe Guymala’s Lorrkon Story, a traditional Aboriginal Australian hollow log “coffin” painted with natural pigments).

Many of The Phillips Collection's 30 panels from Jacob Lawrence's The Migration Series are part of the Seeing Differently exhibition. Photo by Max Hirshfeld

Galleries dedicated to the identity theme similarly feature varied approaches, yet their juxtaposition allows these works seemingly to comment on each other.

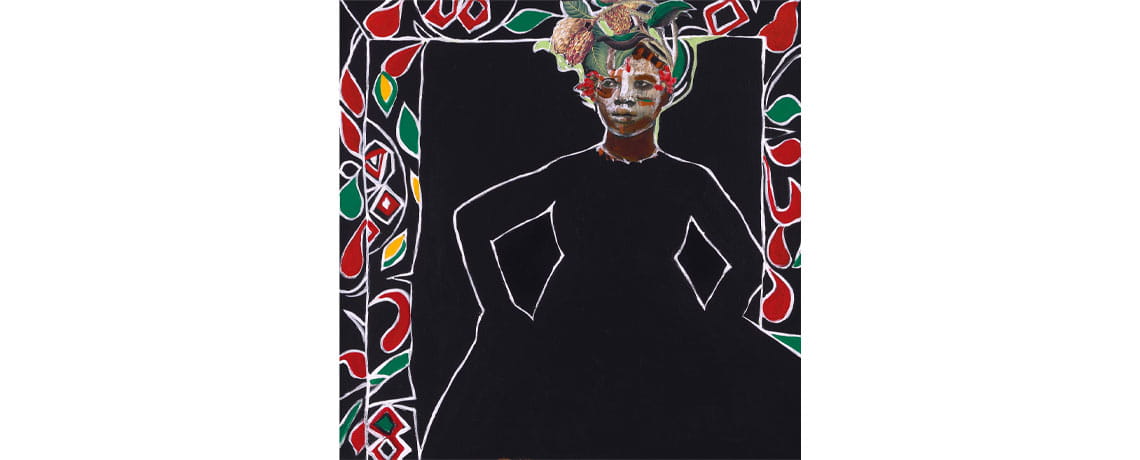

Some works quite literally respond to earlier pieces. And She Was Born (2017) by contemporary African American artist Janet Taylor Pickett draws on the paintings of Henri Matisse, particularly his Interior with Egyptian Curtains, also in the centennial exhibition, to make its own statement about identity.

“There are conversations taking place within a room and conversations that straddle galleries because our architecture allows you to view through archways into other rooms,” Smithgall says. “The idea is to see the works from a multiplicity of perspectives. The concept of unity in diversity guided our thinking as well.”

Reflecting on the timing of the centennial, Phillips Director and CEO Kosinski sums up the promise of this exhibition: “At a time of profound loss and division in our country, the exhibition reminds us of our founder’s abiding belief in the power of art to heal wounds, foster empathy and build community through a greater understanding of our shared humanity—to help us see differently.”

Visit The Phillips Collection at PhillipsCollection.org. For additional information on centennial exhibitions and events, go to AAA.com/morephillips.